In this post, we make the jump from considering only manifolds embedded in cartesian spaces $\bbr^n$ in the style of Guillemin and Pollack’s book (1), to general abstract manifolds which need not be embedded in any ambient space.

To be entirely truthful, I will actually assume that you are already familiar with the definitions and basic rudiments of these general manifolds (i.e., charts, atlases, and all the rest). I admit that this means this series of posts is not entirely self-contained, and that there is left a large gap which the reader needs to fill in for themselves using outside resources. But there are already many fantastic texts on introductory (abstract) manifold theory, and anything I would attempt to write would be at best second-rate in comparison. I will point you toward several of these references below in the section on prerequisites.

So then, what’s the novelty in this post?

While almost all introductions to abstract manifold theory define their manifolds in terms of maximal smooth atlases, I would like to highlight an alternative (but equivalent!) definition of smooth manifolds stated entirely in terms of algebras of functions. The usual charts and atlases are still there of course (the definitions are equivalent, after all), but they are not front and center anymore.

The reason for introducing this algebraic definition of smooth manifolds is not because I believe it is any “better” than the usual one. Rather, it is because it is almost always a good thing to have multiple vantage points on the objects under consideration that I introduce the algebraic definition. The two definitions support and complement each other. While the “charts-and-atlas” definition should certainly come first—that’s the correct pedagogical choice—I believe at some point the algebraic definition should also be presented.

The general method of defining a class of geometric objects by defining the algebras of “allowable” functions on them is common in modern geometry and topology. The most basic object in this paradigm is a so-called ringed space, which consists of a topological space along with a sheaf of rings of “allowable” functions. In considering a smooth manifold $M$, this sheaf is taken to be the sheaf of smooth functions $C^\infty_M$, already familiar to us from the previous post, at least in the embedded case. But by simply changing the sheaf of rings, one obtains other types of geometries: real analytic, complex holomorphic, algebraic, etc. So, if nothing else, in this sense this “ringed space” approach to smooth manifolds unites it with other types of geometries. If unity is something that you appreciate in mathematics, then I think you’ll like the approach taken in this post!

4.1. prerequisites

The previous post is a certain prerequisite. Beyond that, as I mentioned above, in order to read this post, you’ll need to know something about the traditional “charts-and-atlas” definition of smooth manifolds. I would recommend Lee’s book (2). In particular, you should know the definitions and basic results regarding submanifolds, immersions, submersions, and embeddings.

We encountered sheaves in a very informal way in the previous post. In this post, however, I will be defining these gadgets “for real.” Since they are defined as a certain type of functor on a category, it will be helpful to be familiar with the basic definitions of these objects.

4.2. sheaves in general

A presheaf is nothing but a mathematical bookkeeping device that helps us make sense of a “function” that assigns “objects” to all the open sets of a topological space, in such a manner that inclusions of open sets yield restriction maps on the “objects.” The two examples that we saw in the previous post were the assignments $U\mapsto C^\infty(U)$ and $U \mapsto \calx(U)$, where $C^\infty(U)$ is the commutative $\bbr$-algebra of all smooth functions on an open set $U$ of a manifold $M$, and $\calx(U)$ is the $C^\infty(U)$-module of all vector fields over $U$. This is all formalized by defining a presheaf as a type of contravariant functor.

Before we state the precise definition, however, I need to define a concrete category. While the technical definition is here, it is enough for us to understand that a concrete category is (roughly) a category $\sfc$ whose objects are sets with additional “structure,” and where a morphism in $\sfc$ is a set-theoretic function that preserves the additional “structures” of the objects. The primary examples that I have in mind are certain algebraic categories, where $\sfc$ is the category of abelian groups, or commutative $\bbr$-algebras, or modules over an algebra, etc. You will not miss out on much if you think of one of these categories when you see a concrete category $\sfc$. In fact, I will assume each object of $\sfc$ has an underlying set.

Given a topological space $X$, I also need to define a category denoted $\Open(X)$, manufactured from the open sets in $X$. Precisely, the objects of this category are the open sets of $X$, and the morphism sets are given by

\begin{equation}\notag \Hom_{\Open(X)}(U,V) = \begin{cases} \text{inclusion map $U\to V$} & : U\subseteq V, \\ \emptyset & : U\not\subseteq V. \end{cases} \end{equation}

Now, the formal definition:

Definition. Let $X$ be a topological space and $\sfc$ a concrete category. We define a $\sfc$-valued presheaf on $X$ to be a contravariant functor $\calf: \Open(X) \to \sfc$. Given an open set $U\subseteq X$, an element $\sigma \in \calf(U)$ is called a section over $U$.

It will also often be convenient to refer to $\calf$ with “values in the category $\sfc$.” For example, we will say that $\calf$ is a “presheaf of commutative $\bbr$-algebras” to mean that it is a $\sfc$-valued presheaf where $\sfc$ is the category of commutative $\bbr$-algebras.

Thus, to every inclusion $U\subseteq V$ of open sets in $X$, a $\sfc$-valued presheaf $\calf$ assigns a morphism

\begin{equation}\notag \rho^V_U \defeq \calf(U \subseteq V) : \calf(V) \to \calf(U) \end{equation}

in $\sfc$, that we call a restriction map. That $\sfc$ is a functor simply means that $\rho^U_U$ is the identity morphism on $\calf(U)$ for all open sets $U$, and that if $U\subseteq V\subseteq W$ is a nested sequence of open sets in $X$, we have

\begin{equation}\notag \rho^W_V = \rho^V_U \circ \rho^W_V. \end{equation}

Now, a sheaf is nothing but a presheaf that satisfies two additional axioms, naturally called the sheaf axioms:

Definition. Let $X$ be a topological space and $\sfc$ a concrete category. A $\sfc$-valued presheaf $\calf$ on $X$ is called a sheaf if it has the following two properties:

- Suppose that $\{U_i\}_{i\in I}$ is an open cover of an open set $U$ in $X$, and suppose that we have two sections $\sigma,\tau\in \calf(U)$. If \begin{equation}\notag \rho^U_{U_i}(\sigma) = \rho^U_{U_i}(\tau) \end{equation} for all $i\in I$, then $\sigma = \tau$ in $\calf(U)$.

- Suppose again that $\{U_i\}_{i\in I}$ is an open cover of an open set $U$ in $X$, and that for each $i$ we have a section $\sigma_i \in \calf(U_i)$. If these sections agree on overlaps, in the sense that \begin{equation}\notag \rho^{U_i}_{U_i\cap U_j}(\sigma_i) = \rho^{U_j}_{U_i\cap U_j} (\sigma_j) \end{equation} for all $i$ and $j$, then there is a section $\sigma \in \calf(U)$ such that \begin{equation}\notag \rho^U_{U_i}(\sigma) = \sigma_i \end{equation} for all $i$.

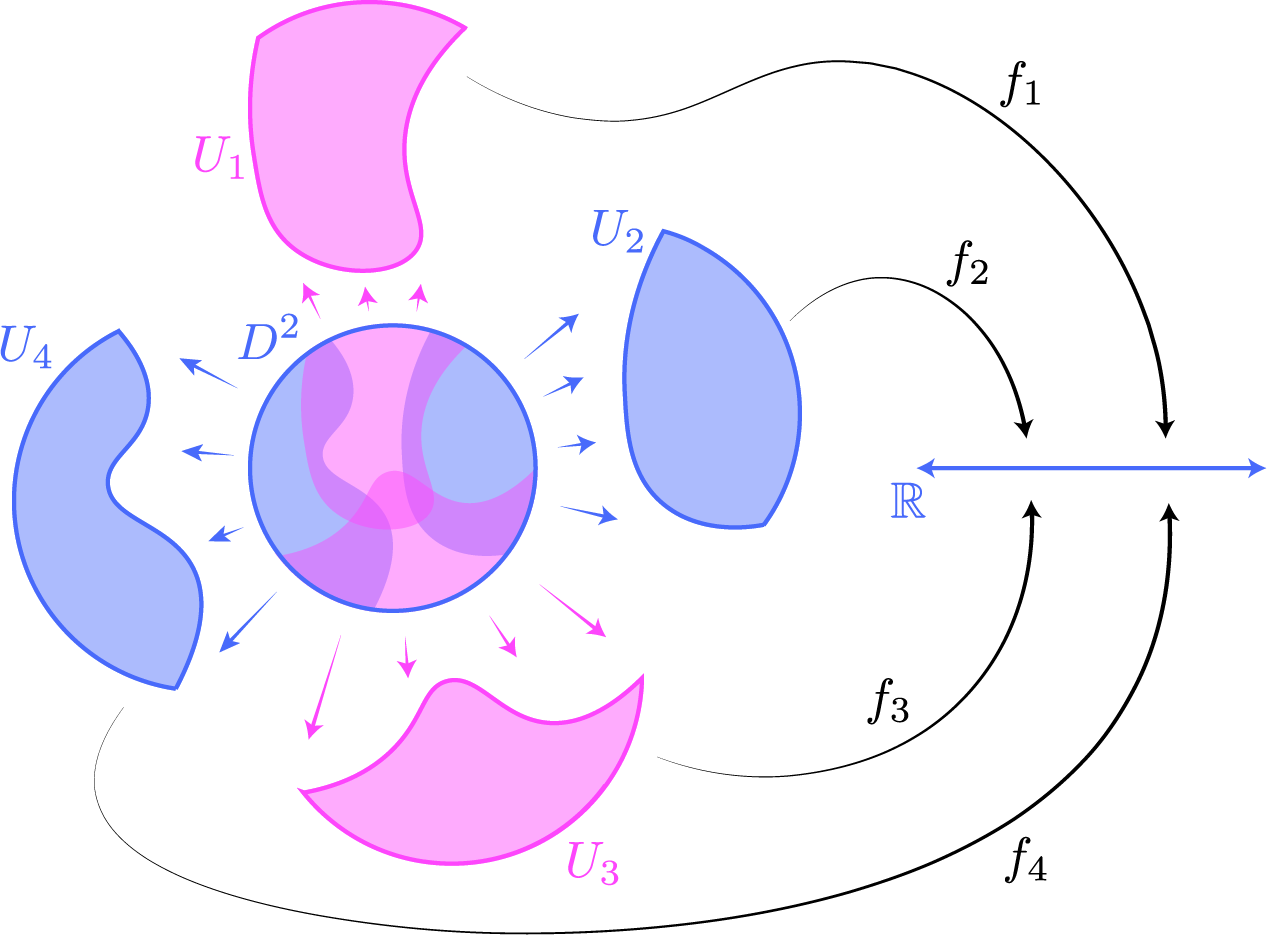

In attempting to wrap your head around property (2.), it is helpful to remember this picture from the previous post:

Here, the topological space is $D^2$, the (solid) unit disk in $\bbr^2$. We have four real-valued functions $f_1,f_2,f_3,f_4$ defined on the open sets $U_1,U_2,U_3,U_4$ of a cover of $D^2$. If we conceive of these functions as sections of some sheaf, then assuming that they agree on overlaps, they “glue” together to yield a global function $f:D^2 \to \bbr$.

While the theory of general sheaves is quite general and extensive, we will use them primarily as organizing devices to help us track “function-like” objects on manifolds, like smooth functions, vector fields, differential forms, and tensor fields more generally. If you understand the basic definitions above, that’s all the sheaf theory you’ll need.

4.3. ringed spaces

While the most general definition of a so-called “ringed space” demands only that the structure sheaf is a sheaf of abstract rings, we will consider only a special case, where the structure sheaf consists of rings of actual functions on a topological space:

Definition. A ringed space is a pair $(X,\calo_X)$ consisting of the following:

- A topological space $X$.

- A sheaf $\calo_X$ on $X$ with values in the category of commutative $\bbr$-algebras. In particular, we require that each $\calo_X(U)$ is a commutative $\bbr$-algebra of real-valued, continuous functions $f:U \to \bbr$ that contains $\bbr$ as the subalgebra of all constant functions.

The sheaf $\calo_X$ is called the structure sheaf of the ringed space.

A morphism of ringed spaces, denoted $\alpha:(X,\calo_X) \to (Y,\calo_Y)$, is a continuous map $\alpha:X \to Y$ such that for each open set $V$ in $Y$, the function

\begin{equation}\notag \alpha^\ast_V: \calo_Y(V) \to \calo_X(\alpha^{-1}(V)), \quad f \mapsto f\circ \alpha, \end{equation}

is well defined, i.e., $f\circ\alpha \in \calo_X(\alpha^{-1}(V))$. In this case, notice that $\alpha_V^\ast$ is a homomorphism of $\bbr$-algebras.

We shall say $\alpha$ is an isomorphism of ringed spaces if the continuous map $\alpha$ is a homeomorphism and its inverse $\alpha^{-1}$ is a morphism of ringed spaces.

This is quite an abstract definition. To help keep your feet on the ground, I recommend doing the following:

Exercise. Let $M$ be a manifold (defined in the style of Guillemin and Pollack) and let $C^\infty_M$ be its sheaf of smooth functions from the previous post. Convince yourself that the pair $(M,C^\infty_M)$ is a ringed space. If $\alpha:M \to N$ is a smooth map between manifolds, prove that it is a morphism of ringed spaces.

If you fully internalized the discussion regarding local rings of manifolds in the previous post, the next definition should look familiar!

Definition. Let $(X,\calo_X)$ be a ringed space. Given a point $p\in X$, let $U$ and $V$ be two open neighborhoods of $p$. Given functions $f\in \calo_X(U)$ and $g\in \calo_X(V)$, we define $f$ and $g$ to be equivalent if there exists an open neighborhood $W$ of $p$ contained in $U\cap V$ such that $f(q) = g(q)$ for all $q\in W$.

One may easily show that this notion of equivalence yields an equivalence relation on the set

\begin{equation}\notag \left\{ f:U \to \bbr : \text{$f \in \calo_X(U)$ and $U$ an open neighborhood of $p$}\right\}. \end{equation}

The equivalence class of a function $f\in \calo_X(U)$ in this set will be written as $(U,f)$. We call the equivalence class $(U,f)$ the germ of $f$ (at $p$), and we write $\calo_{X,p}$ for the set of all such germs.

Exercise. Prove that the set of germs $\calo_{X,p}$ is a commutative $\bbr$-algebra with respect to the evident operations. (If these operations are not “evident” to you, have a look at the previous post!) The ring $\calo_{X,p}$ is called the stalk of $\calo_X$ at $p$.

So, apparently the local rings $C^\infty_{M,p}$ that we studied in the previous post are also called stalks. These were called local rings in the previous post because, of course, they actually were local rings, i.e., they had a unique maximal ideal. In the general case of ringed spaces, we have to add this local condition as an extra property in order to properly refer to stalks as local rings:

Definition. A locally ringed space is a ringed space $(X,\calo_X)$ such that each stalk $\calo_{X,p}$ is a local commutative $\bbr$-algebra. The maximal ideal of this local ring will be denoted $\mfm_{X,p}$.

Exercise. Let $\calo_{X,p}$ be a local ring of a locally ringed space. Define the evaluation map

\begin{equation}\notag \dev_p: \calo_{X,p} \to \bbr, \quad (U,f) \mapsto f(p). \end{equation}

- Prove that $\dev_p$ is a well-defined homomorphism of $\bbr$-algebras.

- Prove that $\mfm_{X,p} = \ker{\dev_p}$, and therefore conclude that $\bbr \cong \calo_{X,p}/\mfm_{X,p}$ as $\bbr$-algebras.

- Let $\alpha:(X,\calo_X) \to (Y,\calo_Y)$ be a morphism of ringed spaces, where both $(X,\calo_X)$ and $(Y,\calo_Y)$ are locally ringed. Set $\alpha(p)=q$, and define \begin{equation}\notag \alpha^\ast_p: \calo_{Y,q} \to \calo_{X,p}, \quad (U,f)\mapsto (\alpha^{-1}(U), f\circ \alpha). \end{equation} Prove that $\alpha^\ast_p$ is a homomorphism of local commutative $\bbr$-algebras, i.e., that it is a homomorphism of algebras such that \begin{equation}\notag \alpha^\ast_p(\mfm_{Y,q}) \subseteq \mfm_{X,p}. \end{equation}

- Prove that the map in (3.) induces a well-defined $\bbr$-linear map \begin{equation}\notag \alpha^\ast_p : \mfm_{Y,q}/\mfm_{Y,q}^2 \to \mfm_{X,p}/\mfm_{X,p}^2 \end{equation} which we denote (via an abuse of notation) also by $\alpha^\ast_p$.

In the notation of the exercise, the $\bbr$-vector space $\mfm_{X,p}/\mfm_{X,p}^2$ is called (just as in the previous post!) the Zariski cotangent space of $X$ at $p$. The maps in (3.) and (4.) are called pullback maps.

Theorem (Local criterion for isomorphisms). Let $\alpha:(X,\sco_X) \to (Y,\sco_Y)$ be a morphism of locally ringed spaces such that the underlying continuous map $\alpha:X \to Y$ is a homeomorphism. Then $\alpha$ is an isomorphism of locally ringed spaces if and only if for all $p\in X$ the pullback map

\begin{equation}\notag \alpha^\ast_p : \sco_{Y,\alpha(p)} \to \sco_{X,p} \end{equation}

is an isomorphism.

Exercise. It will be worth trying to prove this theorem on your own. One direction is obvious. For the other, supposing that $\beta:Y \to X$ is the inverse of $\alpha$ (as a homeomorphism), you need to prove that the pullback map

\begin{equation}\notag \beta^\ast_U: \sco_X(U) \to \sco_Y(\beta^{-1}(U)), \quad f \mapsto f\circ \beta, \end{equation}

is well-defined for all (nonempty) open sets $U$ in $X$, i.e., you must prove that

\begin{equation}\notag f\in \sco_X(U) \quad \Rightarrow \quad f\circ \beta \in \sco_Y(\beta^{-1}(U)). \end{equation}

One point of particular concern for us will be submanifolds. In order to properly define their structure sheaves, we need to introduce the notion of an inverse image of a sheaf. While there is a much more general definition of this gadget, we will only concern ourselves with inverse images produced by inclusion maps:

Definition. Let $Y$ be a (nonempty) subspace of a topological space $X$ (equipped with the subspace topology), suppose $(X,\sco_X)$ is a ringed space, and let $\iota:Y \to X$ be the inclusion map. The inverse image of $\sco_X$, denoted $\iota^{-1}\sco_X$, is the sheaf of $\bbr$-valued functions on $Y$ defined as follows. If $V\subseteq Y$ is a nonempty open set, we define $(\iota^{-1}\sco_X)(V)$ to consist of those $\bbr$-valued functions $f:V\to \bbr$ with the property that for all $p\in V$, there is an open neighborhood $U$ of $p$ in $X$ and a function $\tl{f} \in \sco_X(V)$ such that $f = \tl{f}$ on $U\cap V$.

Exercise. Let the notation be as in the definition.

- Prove that the pair $(Y,\sco_Y)$ is a ringed space, where $\sco_Y = \iota^{-1}\sco_X$.

- Prove that the inclusion induces a morphism \begin{equation}\notag \iota:(Y,\sco_Y) \to (X,\sco_X) \end{equation} of ringed spaces.

- For each $p\in Y$, prove that the pullback map \begin{equation}\notag \iota^\ast_p : \sco_{X,p} \to \sco_{Y,p} \end{equation} is a surjection. Conclude that if $(X,\sco_X)$ is locally ringed, then so is $(Y,\sco_Y)$.

- Supposing that $(X,\sco_X)$ is locally ringed—and hence so is $(Y,\sco_Y)$—prove that for each $p\in Y$ the pullback map \begin{equation}\notag \iota^\ast_p: \mfm_{X,p}/\mfm_{X,p}^2 \to \mfm_{Y,p}/\mfm_{Y,p}^2 \end{equation} is a surjection.

The inverse image of the structure sheaf is defined for an arbitrary subspace. But what does the inverse image look like if the subspace is open?—or closed?

In the case of open subspaces, the answer is easy. We will address closed ones in the special case of manifolds in the next section.

Theorem (Inverse image sheaves on open subspaces.) Let $(X,\sco_X)$ be a ringed space, suppose $U\subseteq X$ is a nonempty open subset, and let $\iota:U \to X$ be the inclusion map. If $V\subseteq U$ is an open subset, then

\begin{equation}\notag (\iota^{-1}\sco_X)(V) = \sco_X(V). \end{equation}

Exercise. Let the notation be as in the theorem.

- Prove the theorem.

- Set $\sco_U = \iota^{-1}\sco_X$. For each $p\in U$, prove that the pullback map \begin{equation}\notag \iota^\ast_p : \sco_{X,p} \to \sco_{U,p} \end{equation} is an isomorphism.

- For each $p\in U$, prove that the pullback map \begin{equation}\notag \iota^\ast_p: \mfm_{X,p}/\mfm_{X,p}^2 \to \mfm_{U,p}/\mfm_{U,p}^2 \end{equation} is an isomorphism.

4.4. abstract manifolds as locally ringed spaces

We define manifolds as particular types of locally ringed spaces, which are locally modeled by cartesian spaces. These latter model spaces are of the form $(\bbr^n,C^\infty_{\bbr^n})$, where $C^\infty_{\bbr^n}$ is the sheaf of smooth functions on $\bbr^n$, in the traditional sense.

Definition. An $n$-dimensional smooth manifold is a locally ringed space $(M,C^\infty_M)$ with the following properties:

- The topological space $M$ is second countable and Hausdorff.

- The space $M$ is covered in open sets $U$ with the property that the ringed space $(U,C^\infty_U)$ is isomorphic to $(V,C^\infty_V)$, where $V$ is an open subset of $\bbr^n$.

In the second property, the structure sheaves $C^\infty_U$ and $C^\infty_V$ are the inverse images of the structure sheaves $C^\infty_M$ and $C^\infty_{\bbr^n}$ under the inclusions $U\subseteq M$ and $V\subseteq \bbr^n$.

A smooth map between smooth manifolds is a morphism $\alpha:(M,C^\infty_M) \to (N,C^\infty_N)$ of ringed spaces.

When we need not mention the structure sheaf, we will often refer to just the topological space $M$ as a manifold, when we really mean the pair $(M,C^\infty_M)$.

While the definition is beautifully concise, one often still needs to get their hands dirty with the usual definition in terms of (maximal) smooth atlases. In particular, when one wants to actually compute things or show that a given topological space is a smooth manifold, atlases and local coordinates are often preferable.

The two definitions are entirely equivalent. Indeed, if $M$ is a smooth $n$-dimensional manifold defined in the traditional way via a maximal smooth atlas, then we define the structure sheaf $C^\infty_M$ by letting $C^\infty_M(U)$ be the commutative $\bbr$-algebra of smooth functions on $U$ in the usual sense, i.e., those functions that are smooth at each point of $U$ with respect to some—and hence any—local coordinate system.

Conversely, suppose that $(M,C^\infty_M)$ is a smooth $n$-dimensional manifold in our sense. Charts in a smooth atlas may be obtained by taking the isomorphisms appearing in part (2.) of the definition. Essentially, then, all we need to show is that if

\begin{equation}\notag \psi_1:(U_1,C^\infty_{U_1}) \to (V_1, C^\infty_{V_1}) \quad \text{and} \quad \psi_2:(U_2,C^\infty_{U_2}) \to (V_2, C^\infty_{V_2}) \end{equation}

are two such isomorphisms with $U_1 \cap U_2\neq \emptyset$, then the composite $\psi_2 \circ \psi_1^{-1}$ is smooth. But this follows from the next exercise:

Exercise. Let $W_1$ and $W_2$ be nonempty, open subsets of $\bbr^n$. Prove that a continuous map $\phi:W_1 \to W_1$ is smooth (in the usual sense) if and only if it is a morphism $\phi:(W_1,C^\infty_{W_1}) \to (W_2,C^\infty_{W_2})$ of ringed spaces. (Hint: One direction is obvious. For the other, make use of the global coordinate functions on $\bbr^n$.)

Then, explain how this result shows that the composite $\psi_2 \circ \psi_1^{-1}$ from above is smooth in the usual sense.

The tangent and cotangent spaces of a smooth manifold (in our sense) are defined via Zariski tangent and cotangent spaces. In particular, if $(M,C^\infty_M)$ is a smooth manifold and $p\in M$ is a point, then the cotangent space at $p$ is defined to be the Zariski cotangent space

\begin{equation}\notag T_p^\ast(M) \defeq \mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2, \end{equation}

where $\mfm_{M,p}$ is the maximal ideal of the local ring $C^\infty_{M,p}$. The tangent space is then the $\bbr$-linear dual of the cotangent space:

\begin{equation}\notag T_p(M) \defeq (\mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2)^\ast. \end{equation}

If $\alpha:(M,C^\infty_M) \to (N,C^\infty_N)$ is a smooth map between manifolds and $\alpha(p)=q$, the pullback map

\begin{equation}\label{fire1-eqn} \alpha_p^\ast: T^\ast_q(N) \to T^\ast_p(M) \end{equation}

is the map on Zariski cotangent spaces induced by the pullback map on local rings

\begin{equation}\label{fire2-eqn} \alpha_p^\ast: C^\infty_{N,q} \to C^\infty_{M,p}. \end{equation}

Again, here we are committing the standard abuse of notation by using the same symbol to represent both pullbacks \eqref{fire1-eqn} and \eqref{fire2-eqn}. The pushforward map is the $\bbr$-linear dual of the pullback \eqref{fire1-eqn}:

\begin{equation}\notag \alpha_{\ast,p} \defeq (\alpha_p^\ast)^\ast : T_p(M) \to T_q(N). \end{equation}

As we learned in the previous post, there are natural isomorphisms

\begin{equation}\notag T_p(M) \cong \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{M,p},\bbr), \end{equation}

and hence our definition of tangent spaces is the same (up to natural isomorphism) as the one more commonly given in introductory textbooks in terms of derivations.

Let’s now discuss submanifolds in the setting of locally ringed spaces. We recall that a smooth map

\begin{equation}\notag \alpha:(M,C^\infty_M) \to (N,C^\infty_N) \end{equation}

is called an immersion at a point $p\in M$ if the pushforward

\begin{equation}\notag \alpha_{\ast,p}: T_p(M) \to T_q(N) \end{equation}

is injective, where $q = \alpha(p)$. We say that $\alpha$ is an immersion if it is an immersion at every point $p\in M$.

Definition. Let $(N,C^\infty_N)$ and $(M,C^\infty_M)$ be two smooth manifolds, suppose that $N$ is a subset of $M$, and let $\iota:N \to M$ be the inclusion map.

- We shall say $N$ is an immersed submanifold of $M$ if $\iota$ is a smooth immersion.

- We shall say $N$ is an embedded submanifold of $M$ if it is an immersed submanifold and the topology on $N$ is the subspace topology inherited from $M$.

- We shall $N$ is a properly embedded submanifold of $M$ if it is an embedded submanifold and is closed in $M$.

The next important theorem describes the structure sheaves of embedded submanifolds.

Theorem (Structure sheaves of embedded submanifolds). Let $(N,C^\infty_N)$ and $(M,C^\infty_M)$ be two smooth manifolds, suppose that $N$ is a topological subspace of $M$, and suppose that the inclusion map induces a smooth map

\begin{equation}\notag \iota: (N,C^\infty_N) \to (M,C^\infty_M). \end{equation}

Then the following conditions are equivalent:

- The manifold $N$ is an embedded submanifold of $M$.

- For each $p\in N$, the pullback \begin{equation}\notag \iota_p^\ast: T_p^\ast(M) \to T_p^\ast(N) \end{equation} on cotangent spaces is surjective.

- For each $p\in N$, the pullback \begin{equation}\notag \iota_p^\ast: C^\infty_{M,p} \to C^\infty_{N,p} \end{equation} on local rings is surjective.

- There is an equality of sheaves $C^\infty_N = \iota^{-1}C^\infty_M$.

(1) $\Leftrightarrow$ (2): Since the topology on $N$ is the subspace topology, it is an embedded submanifold if and only if the inclusion $\iota$ is an immersion. But, $\iota$ is an immersion if and only if the induced maps on cotangent spaces are surjections.

(3) $\Rightarrow$ (2): Clear.

(4) $\Rightarrow$ (3): This was established in an exercise in the previous section.

(1) $\Rightarrow$ (4): Letting $V\subseteq N$ be open, we will prove

\begin{equation}\notag C^\infty_N(V) = \left(\iota^{-1}C^\infty_M\right)(V) \end{equation}

by establishing the two containments “$\subseteq$” and “$\supseteq$”.

For the first one, we let a function $f\in C^\infty_N(V)$ be given. For each $p\in V$, we need to prove that there is an open set $U\subseteq M$ containing $p$ and a function $g \in C^\infty_M(U)$ such that $f=g$ on $U\cap V$. Now, since $\iota$ is an immersion, by shrinking $V$ if needed, through the Constant Rank Theorem we obtain an open set $U\subseteq M$ containing $p$, local coordinates $x^1,\ldots,x^n$ on $V$, local coordinates $x^1,\ldots,x^m$ on $U$ (with $m\geq n$) such that $\iota$ is given locally by

\begin{equation}\notag \iota(x^1,\ldots,x^n) = (x^1,\ldots,x^n,0,\ldots,0). \end{equation}

In these coordinates, we define the function $g$ as the composite

\begin{equation}\notag g: U \xrightarrow{\text{proj}} V \xrightarrow{f} \bbr, \end{equation}

where the first map projects onto the first $n$ coordinates of $\bbr^m$. Clearly $f=g$ on $U\cap V$, which is enough to prove the desired containment “$\subseteq$”. I will leave you the task of proving the opposite containment “$\supseteq$”. Once you’ve done so, we can declare: Q.E.D.

It is important to note that, even though we can equip any subset $N$ of a manifold $M$ with the inverse image sheaf $\iota^{-1}C^\infty_{M}$ (where $\iota:N \to \bbr^n$ is the inclusion map), that this does not mean $N$ is an embedded smooth submanifold of $M$. For example, consider the subset $N$ of $\bbr^3$ defined as the solutions to the equation

\begin{equation}\notag x^2+y^2-z^2 = 0. \end{equation}

We can equip $N$ with the structure sheaf $\sco_N = \iota^{-1}C^\infty_{\bbr^3}$, giving it the structure of a locally ringed space, but $N$ is obviously not an embedded submanifold of $\bbr^3$.

The structure sheaf $C^\infty_N$ of an embedded submanifold is very tightly linked to the structure sheaf $C^\infty_M$ of the ambient manifold. When the submanifold is properly embedded, the link is even tighter, expressed as a clean algebraic relation between $C^\infty_M$ and $C^\infty_N$. To describe it, given an open set $U\subseteq M$, we define

\begin{equation}\notag \cali_N(U) = \left\{ f\in C^\infty_M(U) : f(p) = 0, \ \forall p\in U\cap N \right\}. \end{equation}

Notice that $\cali_N(U)$ is an ideal in the ring $C^\infty_M(U)$. The assignment $U\mapsto \cali_N(U)$ is called the ideal sheaf of $N$ in $M$, and is denoted $\cali_N$.

Theorem (Structure sheaves of properly embedded submanifolds). Let $(N,C^\infty_N)$ be a properly embedded submanifold of $(M,C^\infty_M)$, and let $\iota:N \to M$ be the inclusion map. For each open set $U\subseteq M$, the sequence \begin{equation}\notag 0 \to \cali_N(U) \to C^\infty_M(U) \xrightarrow{\iota^\ast_U} C^\infty_N(U\cap N) \to 0 \end{equation} is exact. In other words, the map $\iota^\ast_U$ is surjective and has kernel given by the ideal $\cali_N(U)$.

Since the ideal $\cali_N(U)$ is essentially defined to be the kernel of $\iota^\ast_U$, all that we need to prove is surjectivity of $\iota^\ast_U$. Since the structure sheaf $C^\infty_N$ is the inverse image $\iota^{-1}C^\infty_M$, we see that any function $f\in C^\infty_N(U\cap N)$ extends locally around each point $p\in U\cap N$ to a smooth function on an open subset $V$ of $M$. By intersecting this latter open subset with $U$, we see that $f$ extends locally around each point of $U\cap N$ to an open subset of $U$. This latter remark is relevant because $U\cap N$ is a closed subset in $U$, and it is well known that smooth functions on closed subsets of manifolds may be extended to smooth functions on the ambient manifold (see Lee’s book mentioned in the section on prerequisites). Thus, $f$ extends to a smooth function $g\in C^\infty(U)$. But then $\iota^\ast_U(g) = f$, which is what we wanted to prove. Q.E.D.

There are certain situations in which we can actually compute ideal sheaves. For example, if $N$ happens to be a smooth hypersurface in $M$, we have the following result:

Theorem. Let $(M,C^\infty_M)$ be an $n$-dimensional smooth manifold, and suppose that $0\in \bbr$ is a regular value of a function $h\in C^\infty_M(M)$. Then the fiber $N = h^{-1}(0)$ is an $(n-1)$-dimensional properly embedded submanifold of $M$, with ideal sheaf given by

\begin{equation}\notag \cali_N(U) = (h|_U), \end{equation}

for all open sets $U\subseteq M$.

It is well known that $N$ is indeed a properly embedded submanifold of dimension $n-1$, so we need only prove the claim regarding the ideal sheaf. The proof that we shall give is an elaboration of the lovely argument given here. Suppose that a function $f\in C^\infty_M(U)$ vanishes along $U\cap N$. On the open complement of $U\cap N$ in $U$, we have

\begin{equation}\notag f = (f/h)h, \end{equation}

and so it will suffice to construct a smooth extension of $f/h$ to the intersection $U\cap N$. Now, given a point $p\in U\cap N$, we know that the function $h:M \to \bbr$ is a submersion at $p$, and hence we may select (using the Constant Rank Theorem) local coordinates $x^1,\ldots,x^n$ on an open neighborhood $V$ of $p$ in $U$ and a local coordinate $x^1$ on an open neighborhood of $0$ in $\bbr$ such that

\begin{equation}\notag h(x^1,\ldots,x^n) = x^1, \quad p=(0,\ldots,0), \end{equation}

and $f(0,x^2,\ldots,x^n)=0$ for all $x^2,\ldots,x^n$. However, by the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, we have

\begin{equation}\notag f(x^1,\ldots,x^n) = x^1 \int_0^1 \frac{\bd f}{\bd x^1}(tx^1,x^2,\ldots,x^n) \ dt. \end{equation}

Thus, in these local coordinates, the quotient $f/h=f/x^1$ may be extended to $p$ by the smooth function

\begin{equation}\notag g(x^1,\ldots,x^n) = \int_0^1 \frac{\bd f}{\bd x^1}(tx^1,x^2,\ldots,x^n) \ dt. \end{equation}

Thus, we see that there is an open covering $\{V_i\}_{i\in I}$ of $U\cap N$ by open sets in $U$ with the property that for each $i\in I$, there exists a smooth function $g_i\in C^\infty_M(V_i)$ such that $f = g_i h$ on $V_i$. If we append the complement $U\smallsetminus (U\cap N)$ to this open cover, in fact we have an open cover $\{V_i\}_{i\in I}$ of the entire set $U$ and smooth functions $g_i \in C^\infty_M(V_i)$ such that $f = g_ih$ on each $V_i$. If we let $\{\psi_i\}_{i\in I}$ be a partition of unity subordinate to the cover $\{V_i\}_{i\in I}$, then we have the desired factorization

\begin{equation}\notag f = \left( \sum_{i\in I} \psi_i g_i \right) h \end{equation}

as functions in $C^\infty_M(U)$. Q.E.D.

Using the theorem, we see, for example, that the algebra of smooth functions on the sphere $S^2$ is given by

\begin{equation}\notag C^\infty(S^2) \cong \frac{C^\infty(\bbr^3)}{(x^2+y^2+z^2-1)}, \end{equation}

where the isomorphism is induced by the restriction map $\rho: C^\infty(\bbr^3) \to C^\infty(S^2)$.