This is the first of four posts devoted to the algebraic side of smooth manifold theory. These posts will be longer and more comprehensive than all the others on my website, due to two primary reasons:

- This material is spread throughout many references, that all use slightly different language and notation, and several of the references are quite advanced, making them difficult to consult for beginners.

- My mathematical specialization is in the intersection of algebra and geometry, so I quite like this stuff. ;)

While the posts on this website are (at least ostensibly) directed at applications in machine learning, my scope here is plainly much more general. Perhaps mathematicians, physicists, and other mathematically-inclined scientists and engineers might find something that interests them. My ultimate goal—to be achieved in the fourth and last post of this subseries of posts—is to offer the reader a careful and thorough treatment of tensor fields on manifolds, one that embraces algebra and its incredibly precise and expressive language to a much greater degree than is typical of most references at the introductory level.

My goal in this very first post, however, is to undertake an in-depth algebraic study of vector fields on manifolds. In a sense, these are the simplest type of tensor fields, though their general tensor nature will not come through until later posts.

\begin{equation}\notag \ast\quad\quad\quad\ast\quad\quad\quad\ast \end{equation}

Before we begin, let me offer an extended introduction to serve as a preview of what’s to come, while introducing some key ideas and buzzwords that will be defined throughout the next few posts.

Abstract algebra plays a prominent role in introductions to manifold theory, but mainly in its linear-algebraic form, embodied through vector spaces and their linear transformations. A little later on, if one continues their study of manifolds, one might encounter other subfields of abstract algebra, perhaps through Lie theory, which fuses linear algebra (Lie algebras) with group theory (Lie groups) via infinitesimal symmetry.

However, as one builds up more complex algebraic structures on manifolds, an equally complex and expressive framework is needed in order to organize and contain them. I have in mind the various intricate tensor fields on manifolds, along with vector bundles, which play a fundamental and crucial role in more advanced treatments of manifolds that go beyond introductory material. In a first encounter with tensors, one is initially struck by their extreme flexibility, capable as they are of representing not only vector fields and differential forms, but also things like curvature.

This flexibility comes with a price, however. A perusal of the popular references might lead one to believe that there are as many definitions of tensors as there are textbook authors. Depending on what applications are under consideration, it might be more beneficial to think of tensors this way, rather than that way, and though the two (or more) ways of thinking of tensors are equivalent, it seems nobody goes through the trouble to explain to the poor neophyte exactly why the definitions are equivalent. This leads to absurd situations where the beginner simply memorizes the popular “index juggling” rules for tensors, not really understanding the actual mathematical content of their manipulations.

All tensor fields over a manifold may be defined as global sections of certain types of vector bundles manufactured from the tangent and cotangent spaces of the manifold. These sets of global sections carry algebraic structure in the form of vector spaces, but these linear structures may be enriched to module structures over commutative algebras of smooth functions. A proper algebraic treatment of tensor fields, therefore, demands not only linear algebra, but also commutative algebra, in the form of abstract module and ring theory. A useful (perhaps loose) contrast to keep in mind is that commutative algebra provides the tools, language, and framework to algebraically comprehend a tensor as a unified, global object, whereas linear algebra is used at the infinitesimal level:

\begin{equation}\notag \left\{\text{Commutative algebra} = \text{Global algebra}\right\} \quad \left\{\text{Linear algebra} = \text{Infinitesimal algebra}\right\} \end{equation}

But beyond merely providing a convenient language for describing tensors, there are situations where commutative algebra provides completely algebraic avatars of familiar objects. For example, the tangent space at a point on a manifold is defined (in the style we are initially following, from Guillemin and Pollack’s book) as a certain vector subspace of the ambient cartesian space in which the manifold is embedded. However, as we will see in this post, there are two(!) purely algebraic characterizations of tangent spaces in the language of commutative algebra, their primary feature being their independence of the embedding of the manifold. This opens the door to a definition of tangent spaces that applies to manifolds that are not assumed embedded (at the outset) in any cartesian space.

All the geometric objects that we shall consider—including tensors—will be smooth, in some appropriate sense. But no matter how it is defined, smoothness of an object at a point on a manifold is always a local property, in the sense that it depends only on the behavior of the object in an arbitrary open neighborhood of the point, i.e., smoothness in one neighborhood implies smoothness in them all. Thus, smooth global objects defined on the entire manifold may be restricted to smooth objects defined on open submanifolds. A common problem is to reverse this restriction process to the corresponding extension process:

- When is it possible to extend a locally defined smooth object to a global one?

- And, if we are given a collection of smooth objects defined on an open cover of the manifold, when do they “glue together” to yield a globally smooth object?

Questions of this type suggest investigations of certain local rings and their modules, which will play a prominent role in this and later posts. These latter algebraic gadgets are related to—indeed, they may be derived from—certain mathematical objects called sheaves. So, in addition to all the rings and modules that we will consider, we will also introduce sheaves (in as gentle a way as possible).

In fact, there is a certain type of geometry, modern scheme-theoretic algebraic geometry, in which the relationship between topology and geometry on one hand, and commutative algebra and sheaf theory on the other, is carried to the logical extreme. In this setting, there is an actual (categorical) equivalence between arbitrary commutative rings and certain topological objects called affine schemes, where the ring serves as the set of “functions” on the scheme. A similar equivalence holds for smooth manifolds, though one must restrict the types of rings included in the equivalence. Though the precise formulations and statements of these equivalences are beyond our scope, a thorough understanding of the content and philosophy in these posts will put you well on your way to understanding them.

We shall have occasion in this and later posts to use the rudiments of category theory. For example, the construction of the tangent spaces to a manifold comes along with the attendant construction of pushforwards between tangent spaces. These constructions satisfy certain abstract axioms, which means that together they form a functor from the category of (pointed) manifolds to the category of vector spaces. However, as I mentioned above, we will discuss two purely algebraic ways to construct the tangent spaces. These constructions, too, come along with their associated pushforwards, and hence we obtain two more functors from the category of (pointed) manifolds to the category of vector spaces. Stated precisely, the main goal of this first post is to show that these three functors are actually naturally isomorphic, in the technical, categorical sense. Along the way, we will obtain another pair of functors (for a total of five!) that realize the cotangent spaces of a manifold and the associated pullbacks, and these two will be shown to be naturally isomorphic, as well.

3.1. prerequisites

The geometric and topological prerequisites are contained in the first two posts of this series (here, and here). These posts, in turn, are based on Guillemin and Pollack’s book (1), from which we take our initial definition of a manifold. Thus, it seems appropriate to make the global proclamation:

In this post, we continue to assume that our manifolds are embedded in an ambient cartesian space, in the style of Guillemin and Pollack’s book.

Besides linear algebra, the algebraic prerequisites include a familiarity with the following objects:

- Commutative algebras, their ideals, and the homomorphisms between them.

- Modules over commutative algebras, and their homomorphisms.

- Tensor products of modules, Hom’s, and their functorial properties.

- Local rings.

All this material (and more) is contained in the first two chapters of Atiyah and Macdonald’s text (2), which was actually written to help prepare students to study scheme-theoretic algebraic geometry, which I mentioned above (that’s what I used it for). The material in the third chapter on algebraic localization would be helpful for general culture, but is not strictly required.

Though it will be helpful to have seen the definition of category and functor, prior exposure to category theory proper is not strictly required. The same goes for sheaf theory: Though I will use the term sheaf, it will be in an informal way, and I do not assume you’ve seen them before.

I fear that the reader may initially balk at the rather demanding and intimidating algebraic prerequisites (which certainly extend beyond the material in a typical undergraduate mathematics degree), but I would assure them that the algebraic material is no more difficult to learn and master than smooth manifold theory.

3.2. vector fields

We begin by giving a definition of smooth vector fields that leverages the ambient cartesian space.

Definition. Let $M$ be a manifold embedded in $\bbr^s$. A vector field on $M$ is a function $X: M \to \bbr^s$ such that $X(p)\in T_p(M)$ for all $p\in M$. We shall say $X$ is a smooth vector field if the function $X$ is smooth.

An alternate notation for the vector $X(p)$ is $X_p$. If the vector field happens to be subscripted because it occurs in a collection, like $X_i$, then we will write $X_i|_p$ in place of the cumbersome $(X_i)_p$.

Smooth vector fields on $M$ may be related to the tangent bundle $T(M)$ through the notion of smooth sections. By definition, a section of the tangent bundle $T(M)$ (with projection $\pi$) is a function $\sigma: M \to T(M)$ such that $\pi \circ \sigma = \id_M$, where $\id_M$ is the identity map on $M$. We shall say $X$ is a smooth section if the function $\sigma$ is smooth.

Theorem (Sections of tangent bundles). Let $M$ be a smooth manifold. There is a one-to-one correspondence between smooth vector fields on $M$ and smooth sections of the tangent bundle $T(M)$. This correspondence associates with a smooth vector field $X$ the section

\begin{equation}\notag \widehat{X}:M \to T(M), \quad \widehat{X}(p) = (p,X_p). \end{equation}

To prove the theorem, one needs to check that $X$ and $\widehat{X}$ are smooth simultaneously. You will do this, and more, in the following:

Exercise.

Let $M$ be an $n$-dimensional manifold embedded in $\bbr^s$.

- In the notation of the previous theorem, prove that $X$ is smooth if and only if $\widehat{X}$ is smooth.

- Prove that smoothness of a vector field $X$ is equivalent to smoothness of its (local) component functions, in the following sense. Let

\begin{equation}\notag \bd_1|_p,\ldots,\bd_n|_p\in T_p(M) \end{equation} be a coordinate vector basis at a point $p$ in an open parametrizable subset $U$. For each $p\in U$, we may write

\begin{equation}\notag X_p = X^j(p) \bd_j|_p, \end{equation} for some (unique!) collection of scalars $X^j(p)\in \bbr$ (summation over repeated indices implied). Prove that the restriction of $X$ to $U$ is smooth if and only if each function $X^j:U \to \bbr$ is smooth.

Going forward, it will be convenient to pass back and forth between these two interpretations of smooth vector fields, i.e., as smooth functions into the ambient cartesian space, and as smooth sections of the tangent bundle. In fact, we will often make the passage between the two without explicit comment, and I will not notationally distinguish between $X$ and $\widehat{X}$.

Every manifold $M$ has a distinguished smooth vector field $X_0: M \to T(M)$, called the zero section of the tangent bundle, which maps $p\mapsto (p,0)$. It is easy to see that $X_0$ embeds $M$ diffeomorphically onto the submanifold

\begin{equation}\notag M_0 \defeq \{(p,0)\in T(M) : p\in M\} \end{equation}

of $T(M)$.

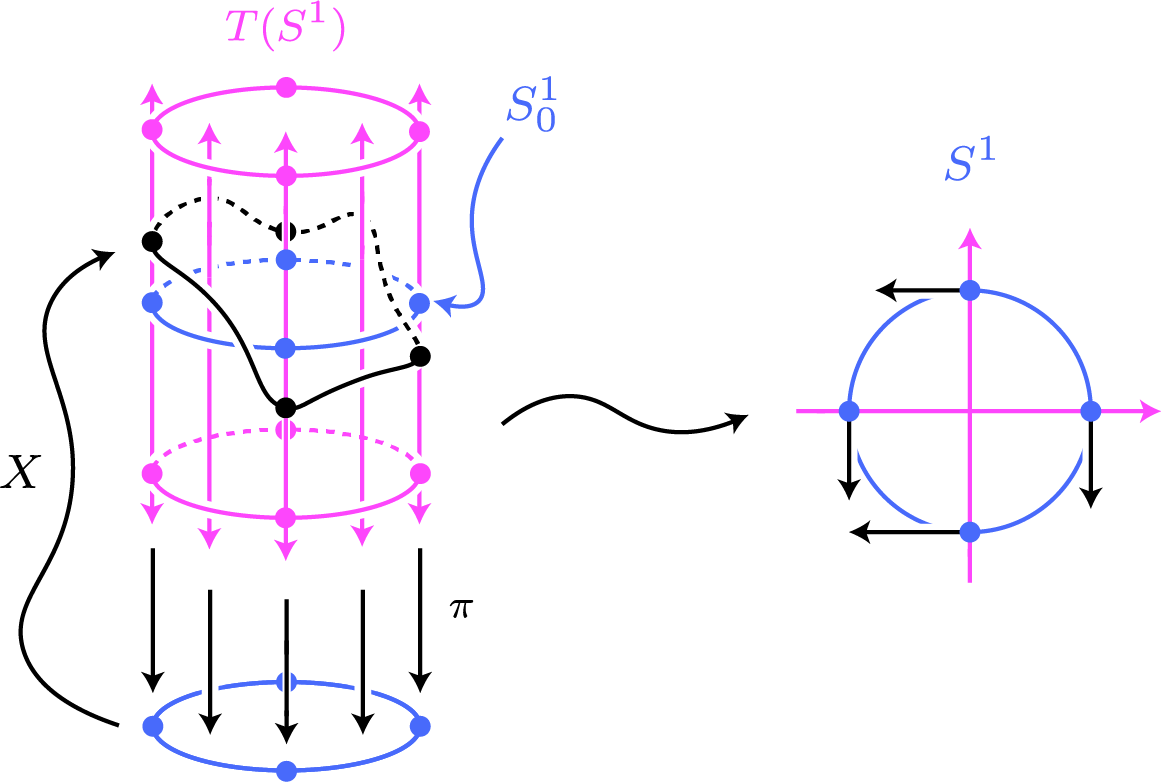

Recall in the previous post our investigations of the tangent bundle $T(S^1)$ of the unit circle $S^1$ in $\bbr^2$. There, we saw that $S^1$ is parallelizable, i.e., there is an isomorphism $T(S^1) \cong S^1 \times \bbr$ of basic vector bundles. We picture the tangent bundle as a cylinder “above” the circle $S^1$, with the canonical projection $\pi:T(S^1) \to S^1$ in a downward orientation. Then, the fiber of $\pi$ over $p\in S^1$, which is the tangent spaces $T_p(S^1)$, is pictured as a vertical line in the cylinder above $p$. We might picture a vector field $X$ on $S^1$, thought of as a section of $T(S^1)$, as follows:

I have drawn the circle $S^1$ embedded (via the zero section) in the tangent bundle as the submanifold $S^1_0$ (in blue). Then, I have chosen orientations in such a way that the portions of the image of $X$ that dip below $S^1_0$ represent vectors on the circle $S^1$ that point in the negative (i.e., clockwise) direction, while portions that are above $S^1_0$ represent vectors that point in the positive direction. It is worth contrasting this version of the vector field $X$ with the following one:

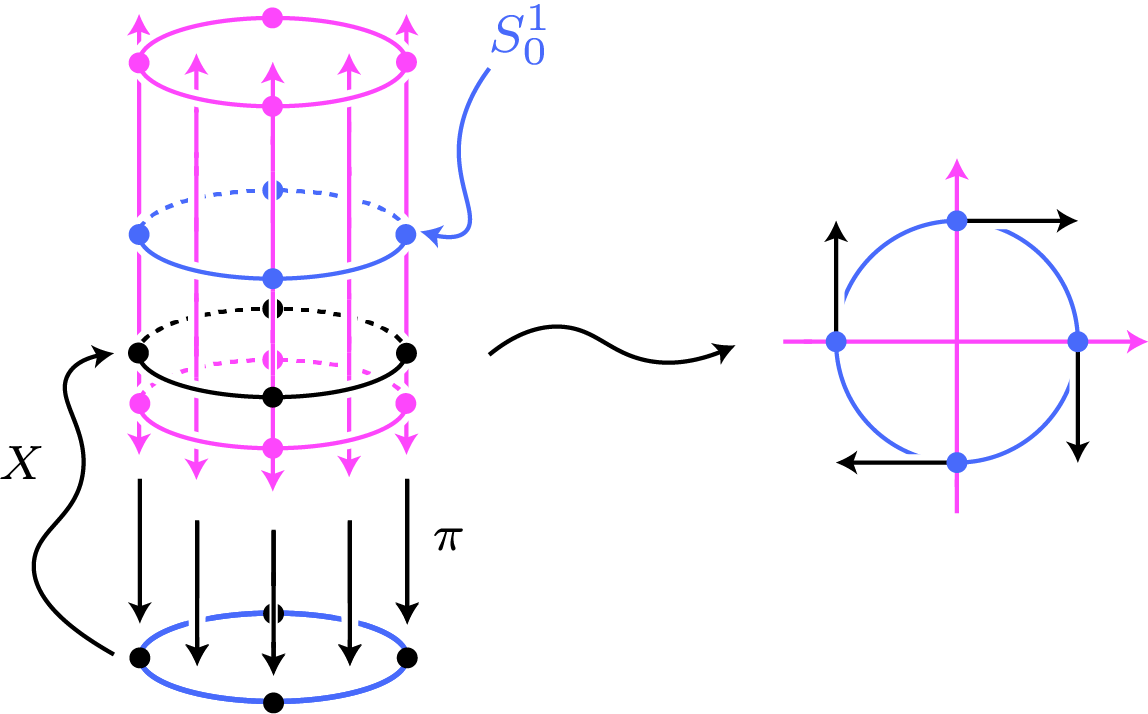

For obvious reasons, this latter version of the vector field $X$ is called horizontal since its image in the tangent bundle is exactly that. It corresponds to a vector field on the circle $S^1$ that is “uniform,” in the sense that it represents the velocity vectors of a particle traveling along $S^1$ in uniform circular motion. The notions of “horizontal,” “uniform,” and “parallel” will be investigated more closely when we talk about Levi-Civita connections in a future post.

Back to the general theory. It is often the case that we must consider smooth vector fields on a manifold $M$ that are only defined on an open set $U$ of $M$. Precisely, such a smooth vector field would be a smooth function $X: U \to T(M)$ such that $\pi \circ X = \id_U$, where $\id_U$ is the identity map on $U$ and $\pi: T(M) \to M$ is the natural projection. In the general language of vector bundles to be introduced later, we call $X$ a (smooth) local section over $U$, in contrast to a vector field defined on the whole of $M$, which is called a (smooth) global section of the tangent bundle.

Definition. Given a manifold $M$, we write $\calx(M)$ for the set of all global smooth sections of the tangent bundle $T(M)$. In other words, $\calx(M)$ is the set of all smooth vector fields on $M$. More generally, if $U$ is an open subset of $M$, then we write $\calx(U)$ for the set of all smooth local sections over $U$.

Since a nonempty open subset $U$ of a manifold $M$ is a manifold in its own right, the notation $\calx(U)$ may be ambiguous. Is it the set of all smooth local sections $X:U \to T(M)$ as just defined, or, instead, is it the set of all smooth global sections $X:U \to T(U)$? Luckily, the ambiguity is only illusory (up to isomorphism), since any smooth local section $X:U \to T(M)$ has the property that

\begin{equation}\notag X_p = (p,v) \in \{p\} \times T_p(M) = \{p\} \times T_p(U) \subset T(U) \end{equation}

for all $p\in U$. Thus, $X$ factors uniquely through a smooth global section of the tangent bundle $T(U)$, and, conversely, any global section of $T(U)$ uniquely induces a local section of $T(M)$ over $U$.

The tangent spaces $T_p(M)$ are all vector spaces, of course, and so each has a basis. It is often very convenient to pick bases in the tangent spaces that vary “smoothly” with the point $p$. This idea is made precise in:

Definition. Let $M$ be an $n$-dimensional manifold and $U\subseteq M$ an open set. A collection of smooth local sections $Y_1,\ldots,Y_n\in \calx(U)$ is called a smooth local frame over $U$ if the vectors $Y_1|_p,\ldots,Y_n|_p \in T_p(M)$ form a basis for each $p\in U$. If $U=M$, then a smooth local frame over $M$ is called a smooth global frame of the manifold.

Smooth local frames exist in plentiful supply on manifolds. In fact:

Theorem (Existence of smooth local frames). Let $M$ be an $n$-dimensional manifold. If the tangent bundle $T(M)$ trivializes over the open set $U\subseteq M$, i.e., if there exists a map \begin{equation}\notag \alpha: U \times \bbr^n \to T(U) \subseteq T(M) \end{equation} which is both a diffeomorphism of smooth manifolds and an isomorphism of basic vector bundles, then a smooth local frame over $U$ exists. In particular, if for each $i=1,\ldots,n$ we define the smooth map \begin{equation}\notag Y_i: U \to T(M), \quad p \mapsto Y_i|_p\defeq (p,\alpha_p(e_i)), \end{equation} where $e_i$ is the $i$-th standard basis vector of $\bbr^n$, then $Y_1,\ldots,Y_n\in \calx(U)$ is a smooth local frame.

You will prove this theorem, among other things, in:

Exercise.

- Prove the previous theorem.

- Let $M$ be an $n$-dimensional manifold and $U\subseteq M$ an open parametrizable set. Prove that the associated coordinate vectors assemble into functions \begin{equation}\notag \bd_i: U \to T(M), \quad p \mapsto \bd_i|_p, \end{equation} such that $\bd_1,\ldots,\bd_n$ is a smooth local frame over $U$. This local frame is called a coordinate local frame, and the function $\bd_i$ is called a coordinate (local) section or coordinate (local) vector field.

- Let $M$ be an $n$-dimensional manifold and $U\subseteq M$ an open set. Prove that a smooth local frame over $U$ exists if and only if $T(M)$ trivializes over $U$.

3.3. a first glimpse of sheaves

Vector fields on manifolds carry very rich algebraic structures, which was hinted at in the previous section. Now, we begin to explore these structures in more detail.

The object underlying the entire algebraic theory of smooth manifolds is the commutative $\bbr$-algebra $C^\infty(M)$ of smooth functions on a manifold $M$. You encountered this object in the first post of this series. There, you also proved that the association $M \mapsto C^\infty(M)$ is functorial, in the sense that if $\alpha:M \to N$ is a smooth map between manifolds, there is an induced pullback map

\begin{equation}\notag \alpha^\ast: C^\infty(N) \to C^\infty(M), \quad f \mapsto \alpha^\ast f \defeq f\circ \alpha, \end{equation}

which is a homomorphism of $\bbr$-algebras. The pullback operation preserves compositions of smooth maps, in the sense that $(\beta \circ \alpha)^\ast = \alpha^\ast \circ \beta^\ast$. This, combined with the observation that the pullback of the identity map is the identity map, shows that diffeomorphic manifolds have isomorphic algebras of smooth functions.

Every nonempty open set $U$ of a manifold $M$ is a manifold in its own right, and hence we may consider the algebra $C^\infty(U)$. As $U$ is an open submanifold of $M$, the inclusion map $\iota:U \to M$ is smooth, and the pullback

\begin{equation}\label{global-eqn} \iota^\ast : C^\infty(M) \to C^\infty(U) \end{equation}

is called a restriction map since it sends a function $f$ on $M$ to the restriction $f|_U$ on $U$. In fact, it will be convenient to generalize the situation slightly. Suppose that we have two open subsets of $M$, say $U$ and $V$, and suppose that $U\subseteq V$. The smooth inclusion map $\iota: U\to V$ induces a pullback

\begin{equation}\label{rest-eqn} \rho^V_U \defeq \iota^\ast: C^\infty(V) \to C^\infty(U) \end{equation}

which is also called a restriction map. The map \eqref{global-eqn} is the special case $\rho^M_U$. If $U$ is the empty set, we let $C^\infty(U)$ be the zero algebra.

If you’d like a little more practice with algebras of smooth functions, I suggest the following exercise:

Exercise. Let $M$ be a manifold.

- Prove that the restriction map $\rho^V_U$ is a homomorphism of $\bbr$-algebras.

- If $U$ is an open set in $M$, prove that the restriction map $\rho^U_U$ is the identity map on $C^\infty(U)$.

- If $U\subseteq V \subseteq W$ are open subsets of $M$, prove that \begin{equation}\notag \rho^W_U = \rho^{V}_U\circ \rho^W_V. \end{equation}

- Suppose $U$ is an open subset of $M$, and that $\{U_i\}_{i\in I}$ is an open cover of $U$ (indexed by a set $I$, with no assumptions placed on it). Prove that if $f,g\in C^\infty(U)$ and $\rho^U_{U_i}(f) = \rho^U_{U_i}(g)$ for all $i\in I$, then $f=g$ as functions in $C^\infty(U)$.

- Continuing with the open cover $\{U_i\}$ from the previous part, suppose that for each $i\in I$ we have a function $f_i \in C^\infty(U_i)$. Suppose further that the $f_i$’s agree on overlaps, in the sense that \begin{equation}\notag \rho^{U_i}_{U_i\cap U_j}(f_i) = \rho^{U_j}_{U_i\cap U_j} (f_j) \end{equation} for all $i,j\in I$. Prove that there is a (necessarily unique!) function $f\in C^\infty(U)$ such that $\rho^U_{U_i}(f) = f_i$ for all $i\in I$.

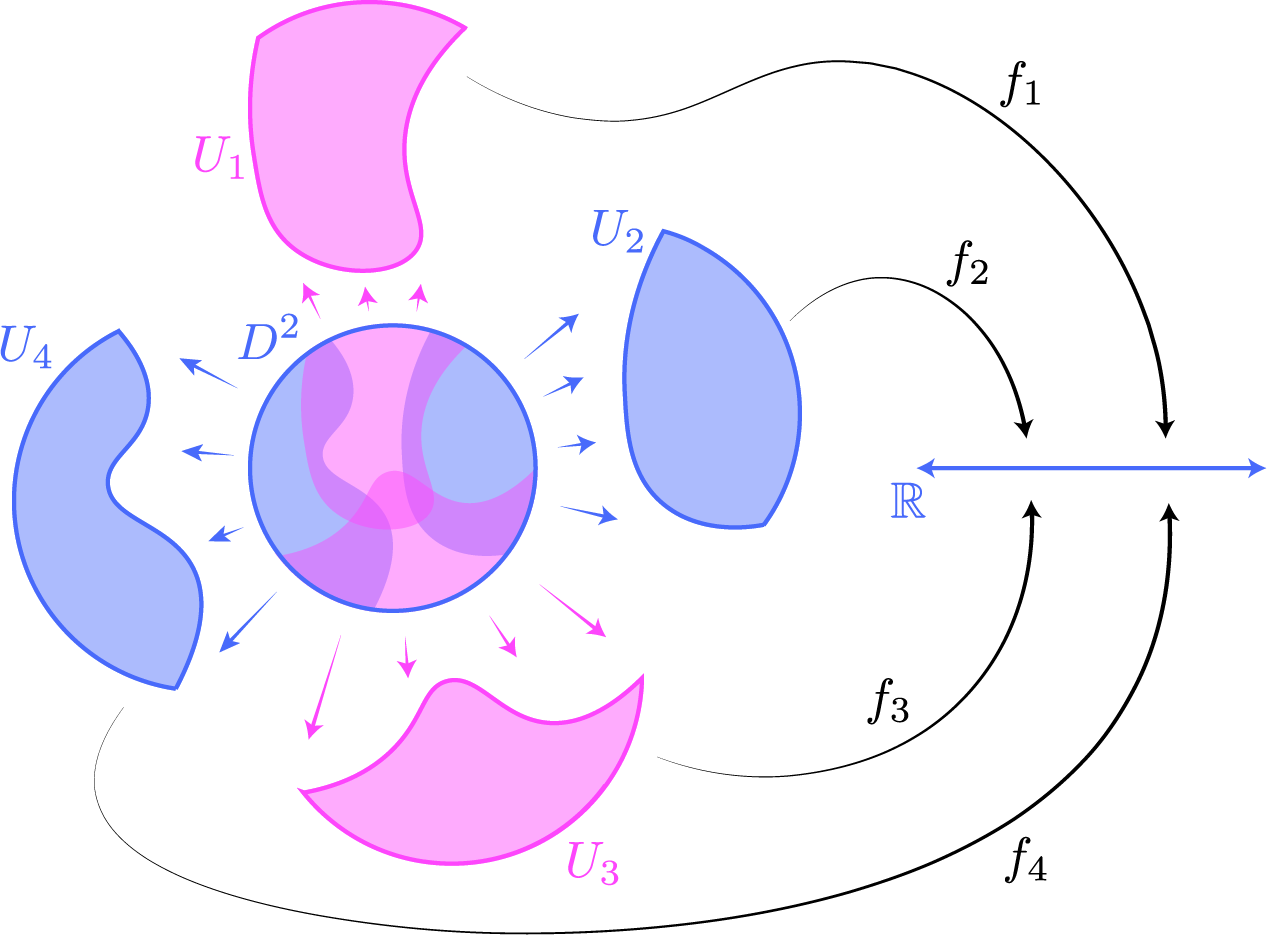

The typical cartoon illustration that goes along with property (5.) is something like:

Here, the manifold is the unit disk $D^2$ in $\bbr^2$, and I’ve drawn an open cover consisting of four sets: $\{U_1,U_2,U_3,U_4\}$. For each set in the cover, we are given a smooth function $f_i: U_i \to \bbr$. If these functions agree on the overlaps of the $U_i$’s, then they “glue” together to yield a smooth function $f:D^2 \to \bbr$.

The verifications in parts (2.)-(4.) of the exercise are more or less trivialities, and do not use any special properties of smooth functions. In fact, these same properties would have been true for any class of functions. In (5.), defining the function $f$ is also a triviality; however, checking that $f$ is smooth crucially uses the fact that smoothness is a local condition, by which I mean that a function $f:M \to \bbr$ is smooth at a point $p\in M$ if and only if there is an open neighborhood $U$ of $p$ such that $f|_U$ is smooth at $p$. There’s a general principle in geometry and topology that any class of functions which is defined via a local condition automatically satisfies the same properties in the exercise.

If you completed the exercise, give yourself a pat on the back, because you have successfully proved that the association $U \mapsto C^\infty(U)$, defined on the open sets of a manifold $M$, is a sheaf of commutative $\bbr$-algebras on $M$. In fact, the individual parts of the exercise are exactly the so-called sheaf axioms. The association $U\mapsto C^\infty(U)$ can be thought of as a type of “function,” though technically it’s actually a certain functor. This “function” is called a sheaf. We will denote it by $C^\infty$, or by $C^\infty_M$ if we need to call attention to $M$. Fancy!

We thus have a way to associate rings to manifolds. But what about modules?

Exercise. Let $M$ be a manifold. Let $\calx(U)$ be the set of local sections of the tangent bundle $T(M)$ over a nonempty open set $U$. Let $X,Y\in \calx(U)$ and $f\in C^\infty(U)$.

- The sum of $X$ and $Y$, denoted $X+Y$, is the vector field defined by \begin{equation}\notag (X+Y)_p = X_p +Y_p. \end{equation}

-

The scalar product of $f$ and $X$, denoted $fX$, is the vector field defined by

\begin{equation}\notag (fX)_p = f(p)X_p. \end{equation}

With respect to these operations, prove that $\calx(U)$ is a $C^\infty(U)$-module.

Since vector fields in $\calx(U)$ are nothing but functions, there are natural restriction maps. In particular, suppose that we have open sets $U$ and $V$ with $U\subseteq V$. We define

\begin{equation}\notag r^V_U : \calx(V) \to \calx(U), \quad X\mapsto X|_U. \end{equation}

The source and target of this map are modules over $C^\infty(U)$ and $C^\infty(V)$, respectively. By restricting scalars along the restriction map \eqref{rest-eqn}, every $C^\infty(U)$-module may be considered a $C^\infty(V)$-module. In particular, $\calx(U)$ is a $C^\infty(V)$-module.

Exercise. Let $M$ be a manifold.

- Prove that the restriction map $r^V_U$ is $C^\infty(V)$-linear.

- If $U$ is an open set in $M$, prove that the restriction map $r^U_U$ is the identity map on $\calx(U)$.

- If $U\subseteq V \subseteq W$ are open subsets of $M$, prove that \begin{equation}\notag r^W_U = r^{V}_U\circ r^W_V. \end{equation}

- Suppose $U$ is an open subset of $M$, and that $\{U_i\}_{i\in I}$ is an open cover of $U$. Prove that if $X,Y\in \calx(U)$ and $r^U_{U_i}(X) = r^U_{U_i}(Y)$ for all $i\in I$, then $X=Y$ as vector fields in $\calx(U)$.

- Continuing with the open cover $\{U_i\}$ from the previous part, suppose that for each $i\in I$ we have a vector field $X_i \in \calx(U_i)$. Suppose further that the $X_i$’s agree on overlaps, in the sense that \begin{equation}\notag r^{U_i}_{U_i\cap U_j}(X_i) = r^{U_j}_{U_i\cap U_j} (X_j) \end{equation} for all $i,j\in I$. Prove that there is a (necessarily unique!) vector field $X\in \calx(U)$ such that $r^U_{U_i}(X) = X_i$ for all $i\in I$.

You should recognize the parts of this exercise as the sheaf axioms that I mentioned above! So, if you completed the exercise, you have proved that the association $U \mapsto \calx(U)$ is a sheaf of $C^\infty$-modules. This sheaf will be denoted $\calx$, or $\calx_M$ if we need to explicitly mention the manifold $M$. Thus, $\calx_M$ is a $C^\infty_M$-module.

Now, I would suggest using a theorem in the previous section to complete the following:

Exercise. Let $U$ be a nonempty open set of an $n$-dimensional manifold $M$. Prove that $\calx(U)$ is a free $C^\infty(U)$-module of rank $n$ if and only if the tangent bundle $T(M)$ trivializes over $U$.

Thus, while the $C^\infty(M)$-module of global sections $\calx(M)$ may not be free (unless the manifold is parallelizable), the manifold $M$ is covered in open sets $U$ for which $\calx(U)$ is free. A fancy way of rephrasing this is: While the sheaf of modules $\calx_M$ may not be free over $C^\infty_M$, it is locally free.

There’s a heuristic in algebra and geometry (which can be made precise, in a few different ways) that “locally free” modules tend to coincide with so-called projective modules. While the latter can be precisely characterized and defined in several ways, it is perhaps best to think of the class of projective modules as a generalization of the class of free modules. The extent to which these two classes of modules do not coincide (over a fixed ring) is often seen as a reflection of the complexity of the internal algebraic structure of the ring. For example, if the ring is a field, then the two classes are equal (i.e., projective $=$ free), which reflects the fact that fields are some of the nicest examples of rings.

While a given projective module may not be free, it still shares several important properties with a free module. Of particular importance for us is that several natural isomorphisms which trivially hold for free modules also hold for (finitely generated) projective modules. These isomorphisms are key to a proper algebraic treatment of tensor fields on manifolds which we will discuss in a future post. For now, let me only mention the following special case of a very famous theorem, which shows that “local freeness” of vector fields does indeed translate to projectivity:

The Serre-Swan Theorem (First version). The set $\calx(M)$ of (smooth) vector fields on a manifold $M$ is a finitely-generated projective module over the commutative $\bbr$-algebra $C^\infty(M)$ of smooth functions.

Again, the importance of this result will become apparent in a later post when we talk about tensor fields. We will not prove the theorem in this series of posts; see, however, the section on Further Reading.

3.4. tangent vectors and vector fields as derivations

Let’s move on to an algebraic description of tangent vectors and vector fields. We essentially have two definitions of a vector field $X$ on a manifold $M$: On the one hand, it is a certain type of smooth map from $M$ to the ambient cartesian space containing the manifold, while on the other hand it may be viewed as a (smooth) section of the tangent bundle $T(M)$. I will give a third definition in this section, and it rests on the observation that a tangent vector $v\in T_p(M)$ “acts” on a function $f\in C^\infty(U)$ defined over an open neighborhood $U$ of $p$ by

\begin{equation}\notag v(f) \defeq f_{\ast,p}(v) \in \bbr. \end{equation}

Viewed in this way as mappings $v:C^\infty(U)\to \bbr$, tangent vectors have three characteristic properties which you may easily prove:

Properties of tangent vectors as mappings.

- The tangent vector $v$ is $\bbr$-linear.

- The tangent vector $v$ satisfies the Leibniz rule (or product rule), which means that \begin{equation}\notag v(fg) = f(p)v(g) + g(p)v(f) \end{equation} for all $f,g\in C^\infty(U)$.

- If $f\in C^\infty(U)$ and $g\in C^\infty(V)$ are two functions defined on open neighborhoods of $p$ that coincide on an open neighborhood $W\subseteq U \cap V$ of $p$, then $v(f) = v(g)$.

The third property is the observation that tangent vectors act locally. This suggests that it’s not the entire global behavior of a function $f$ that determines the value $v(f)$, but rather only its local behavior in a neighborhood of $p$. This suggests that we study the following algebraic structure:

Definition. Let $p$ be a point on a manifold $M$, and let $U$ and $V$ be two open neighborhoods of $p$. Given smooth functions $f\in C^\infty(U)$ and $g\in C^\infty(V)$, we define $f$ and $g$ to be equivalent if there exists an open neighborhood $W$ of $p$ contained in $U\cap V$ such that $f(q) = g(q)$ for all $q\in W$.

One may easily show that this notion of equivalence yields an equivalence relation on the set

\begin{equation}\notag \left\{ f:U \to \bbr : \text{$f$ smooth and $U$ an open neighborhood of $p$}\right\}. \end{equation}

The equivalence class of a function $f:U \to \bbr$ in this set will be written as $(U,f)$. We call the equivalence class $(U,f)$ the germ of $f$ (at $p$), and we write $C^\infty_{M,p}$ for the set of all such germs. The set $C^\infty_{M,p}$ is called the local ring at $p$.

Of course, the name “local ring” for $C^\infty_{M,p}$ must be justified, part of which you will do in the next exercise.

Exercise. Let the notation be as above, and let $f\in C^\infty(U)$, $g\in C^\infty(V)$, and $c\in \bbr$.

- We define the sum of the germs $(U,f)$ and $(V,g)$ to be the germ \begin{equation}\notag (U,f) + (V,g) = (U\cap V, f+g). \end{equation}

- We define the product of the germs $(U,f)$ and $(V,g)$ to be the germ \begin{equation}\notag (U,f) (V,g) = (U\cap V,fg). \end{equation}

- We define the scalar multiple of $c$ with the germ $(U,f)$ to be the germ \begin{equation}\notag c(U,f) = (U,cf). \end{equation}

Prove that these operations are well-defined, and that the resulting structure on $C^\infty_{M,p}$ is a commutative $\bbr$-algebra.

The notation $(U,f)$ for the germ of a function, while being complete and unambiguous, can make certain formulas more cluttered than they otherwise would be if we weren’t dealing with germs. Therefore, when we believe that the reader will not be too bothered by the abuse, we will drop the cumbersome notation $(U,f)$ when convenient and write $f$ in its place.

The next result describes a crucial link between $C^\infty(M)$ and the local ring $C^\infty_{M,p}$.

Theorem (Localization maps). Let $p$ be a point on a smooth manifold $M$ and define

\begin{equation}\notag \lambda: C^\infty(M) \to C^\infty_{M,p}, \quad f \mapsto (M,f). \end{equation}

Then $\lambda$ is a surjective homomorphism of $\bbr$-algebras.

I will leave you to prove that $\lambda$ is a homomorphism of $\bbr$-algebras. For surjectivity, we suppose that a germ $(U,g)$ in the local ring is given. By shrinking $U$ if needed (which does not change the germ), we may extend $g$ by zero to a global function $\tl{g}\in C^\infty(M)$ such that $\tl{g} = g$ on $U$. But then we have $\lambda(\tl{g}) = g$, as desired. Q.E.D.

Having shown that the local ring $C^\infty_{M,p}$ is indeed a ring, you will now show that it is “local” in the algebraic sense of the word:

Exercise. Let the notation be as above.

- Consider the evaluation map given by \begin{equation}\notag \dev_p: C^\infty_{M,p} \to \bbr, \quad f \mapsto f(p). \end{equation} Prove that $\dev_p$ is a well-defined homomorphism of $\bbr$-algebras. (Notice that I am writing $f$, when I really mean the germ represented by $f$!)

- Prove that \begin{equation}\notag \mfm_{M,p} \defeq \ker\dev_p \end{equation} is the only maximal ideal in $C^\infty_{M,p}$, and thus conclude that the latter is a local ring.

Now, one may use the fact tangent vectors act locally to prove the following important result, which shows that the actions of tangent vectors “descend” to the localization:

Theorem (Tangent vectors act locally). Let $p$ be a point on a manifold $M$. Given a tangent vector $v\in T_p(M)$ and a germ $f \in C^\infty_{M,p}$, the formula

\begin{equation}\notag v(f) \defeq f_{\ast,p}(v) \end{equation}

yields a well-defined function $v: C^\infty_{M,p} \to \bbr$ with the following properties:

- The function $v$ is $\bbr$-linear.

- The function $v$ satisfies the Leibniz rule, in the sense that \begin{equation}\notag v\left(fg \right) = f(p) v\left(g \right) + g(p) v\left(f \right) \end{equation}

for all $f,g\in C^\infty_{M,p}$.

Again, notice that I am writing $f$ and $g$ when I really mean the germs represented by these functions!

The theorem shows that tangent vectors are examples of the following general type of algebraic objects:

Definition. Let $A$ be a commutative $\bbr$-algebra and $P$ an $A$-module. A function $\delta:A \to P$ is called a derivation if:

- The map $\delta$ is $\bbr$-linear.

- For all $f,g\in A$, we have $\delta(fg) = f\delta(g) + g\delta(f)$.

The equation in (2.) is called the Leibniz rule. The $\bbr$-vector space of all such derivations is written $\Der_\bbr(A,P)$.

Now, let’s show that tangent vectors do, indeed, yield derivations:

Exercise. Let $p$ be a point on a manifold $M$ and let $\dev_p: C^\infty_{M,p} \to \bbr$ be the evaluation map. By restricing scalars along $\dev_p$, the real line $\bbr$ may be viewed as a $C^\infty_{M,p}$-module. Prove that every tangent vector $v:C^\infty_{M,p} \to \bbr$ is a derivation in $\Der_\bbr( C^\infty_{M,p},\bbr)$.

The association of tangent vectors with derivations has a remarkable property:

Theorem (Tangent spaces $=$ derivations). For each point $p$ on a manifold $M$, the natural $\bbr$-linear map

\begin{equation}\notag \Theta_{M,p}: T_p(M) \to \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{M,p},\bbr), \quad \left[\Theta_{M,p}(v)\right](f) = v(f), \end{equation}

is an isomorphism.

The proof of this theorem will take some work. Essentially, it will go like this:

- Show that both the domain and codomain of the (alleged) isomorphism are unaffected (up to isomorphism) by restricting $M$ to an open parametrizable neighborhood of $p$.

- Leverage “naturality” of the (alleged) isomorphism to then restrict to the case $M=\bbr^n$.

I will actually address step (2.) first, by explaining exactly what “naturality” means in this context.

The point is that the construction $M \mapsto \Der_\bbr(C^{\infty}_{M,p},\bbr)$ is functorial, which means that it can also be applied to smooth maps, and these constructions satisfy a collection of axioms. To explain, suppose that $\alpha:M \to N$ is a smooth map of manifolds with $\alpha(p)=q$. Then, as we know, there is a pushforward map

\begin{equation}\notag \alpha_{\ast,p} : T_p(M) \to T_q(N), \end{equation}

which is an isomorphism provided that $\alpha$ is a diffeomorphism. However, there is also a version of the pushforward on derivations given by

\begin{equation}\notag \alpha_{\ast,p}’ : \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{M,p},\bbr) \to \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{N,q},\bbr), \quad \delta \mapsto \delta \circ {\alpha^\ast_p}’, \end{equation}

where

\begin{equation}\label{towel-eqn} {\alpha^\ast_p}’: C^\infty_{N,q} \to C^\infty_{M,p} \end{equation}

is given by

\begin{equation}\label{towel2-eqn} {\alpha^\ast_p}’(U,g) = \left( \alpha^{-1}(U), g\circ \alpha|_{\alpha^{-1}(U)}\right). \end{equation}

This map ${\alpha^\ast_p}’$ is called a pullback map, since it is the “localization” of the familiar pullback map $\alpha^\ast: C^\infty(N) \to C^\infty(M)$. I have written it with a prime, rather than just $\alpha^\ast_p$, to differentiate it from another type of pullback studied in the next section.

Exercise. Let the notation be as above.

- Prove that ${\alpha^\ast_p}’$ is a well-defined homomorphism of local $\bbr$-algebras.

- Prove that $\alpha_{\ast,p}’$ is a well-defined $\bbr$-linear homomorphism.

- If $M=N$ and $\alpha$ is the identity map $\id_M$, prove that $\alpha_{p,\ast}’$ is the identity map on the space of derivations.

- If $\beta:N \to L$ is a second smooth map, prove that \begin{equation}\notag (\beta\circ \alpha)_{\ast,p}’ = \beta’_{\ast,q}\circ \alpha_{\ast,p}’. \end{equation}

- Conclude that if $\alpha$ is a diffeomorphism, then $\alpha_{\ast,p}’$ is an isomorphism.

- Prove that the natural maps $\Theta_{M,p}$ and $\Theta_{N,q}$ in the previous theorem commute with the two versions of the pushforward, i.e., prove that the diagram \begin{equation}\notag \begin{xy} \xymatrix{ T_p(M) \ar[r]^-{\Theta_{M,p}} \ar[d]_{\alpha_{\ast,p}} & \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{M,p},\bbr) \ar[d]^{\alpha_{\ast,p}’} \\ T_q(N) \ar[r]_-{\Theta_{N,q}} & \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{N,q},\bbr)} \end{xy} \end{equation} commutes.

Thus, we see that the spaces of derivations and the pushfowards $\alpha_{\ast,p}’$ satisfy many of the same important properties as the tangent spaces and the pushforwards $\alpha_{\ast,p}$. This situation may be summarized using the following fancy categorical language:

Definition. A pointed manifold is a pair $(M,p)$ consisting of a point $p$ on a manifold $M$. A morphism of pointed manifolds, denoted $\alpha:(M,p) \to (N,q)$, is a smooth map $\alpha:M \to N$ between manifolds such that $\alpha(p) = q$. The “set” of all pointed manifolds and their morphisms is called the category of pointed manifolds.

Using this language, we see that for every pointed manifold $(M,p)$ there is an associated space of derivations

\begin{equation}\label{funct1-eqn} (M,p) \mapsto \Der_\bbr(C^{\infty}_{M,p},\bbr), \end{equation}

and for every morphism $\alpha:(M,p) \to (N,q)$ there is an associated pushforward

\begin{equation}\label{funct2-eqn} \alpha \mapsto (\alpha_{\ast,p}’ : \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{M,p},\bbr) \to \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{N,q},\bbr)). \end{equation}

Then, properties (2.)-(4.) in the previous exercise may be stated as saying that the associations \eqref{funct1-eqn} and \eqref{funct2-eqn} define a functor from the category of pointed manifolds to the category of vector spaces. On the other hand, to every pointed manifold $(M,p)$ we may also associate the tangent space

\begin{equation}\label{funct3-eqn} (M,p) \mapsto T_p(M), \end{equation}

and to every morphism $\alpha:(M,p) \to (N,q)$ the pushforward

\begin{equation}\label{funct4-eqn} \alpha \mapsto (\alpha_{\ast,p} : T_p(M) \to T_q(N)). \end{equation}

As you may check, these associations \eqref{funct3-eqn} and \eqref{funct4-eqn} satisfy the obvious analogs of properties (2.)-(4.) in the exercise, and so they too define a functor from the category of pointed manifolds to vector spaces. Finally, property (6.) in the exercise shows that the maps $\Theta_{M,p}$ yield a natural transformation between the two functors—even more, after we prove the theorem, they actually yield an isomorphism of functors.

Now that we know exactly what “naturality” of the homomorphism $\Theta_{M,p}$ means, let’s address the other important point, that a restriction to an open subset does not affect a space of derivations:

Theorem (Derivations on open subsets). Let $M$ be a manifold, $U\subseteq M$ a nonempty open subset, $p$ a point in $U$, and $\iota:U \to M$ the (smooth) inclusion map.

- The pullback $\iota_p^\ast: C^\infty_{M,p} \to C^\infty_{U,p}$ is an isomorphism of local $\bbr$-algebras.

- The pushforward \begin{equation}\notag \iota_{\ast,p}’: \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{U,p},\bbr) \to \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{M,p},\bbr) \end{equation} is an $\bbr$-linear isomorphism.

Note that part (2.) follows immediately from part (1.), while (1.) more or less follows straight from the definition of germs of functions. I will leave you to fill in the details.

Let’s now turn toward the proof of the main theorem. Let $U$ be an open parametrizable neighborhood of $p$, diffeomorphic to $\bbr^n$ via a diffeomorphism $\phi:\bbr^n \to U$ with $\phi(x)=p$. Let $\iota:U \to M$ be the (smooth) inclusion map. By naturality, the diagram

\begin{equation}\notag \begin{xy} \xymatrix{ T_p(M) \ar[r]^-{\Theta_{M,p}} & \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{M,p},\bbr) \\ T_p(U) \ar[u]^{\iota_{\ast,p}}_{=} \ar[r]^-{ \Theta_{U,p}} & \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{U,p},\bbr) \ar[u]_{ \iota_{\ast,p}’}^{\cong } \\ T_x(\bbr^n) \ar[r]^-{\Theta_{\bbr^n,x}} \ar[u]^{ \phi_{\ast,x}}_{\cong} & \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{\bbr^n,x},\bbr) \ar[u]_{ \phi_{\ast,x}’}^{\cong} } \end{xy} \end{equation}

commutes. The pushforward $\iota_{\ast,p}$ is actually the identity map, since $T_p(M) = T_p(U)$, while the pushforwards $\phi_{\ast,x}$ and $\phi_{\ast,x}’$ are isomorphisms since $\phi$ is a diffeomorphism and the formation of pushforwards is functorial. The pushforward $\iota_{\ast,p}’$ is an isomorphism by the previous theorem. Thus, in order to prove $\Theta_{M,p}$ is an isomorphism, it will suffice to prove $\Theta_{\bbr^n,x}$ is one.

We may therefore assume that $M=\bbr^n$, without any loss in generality. Let $x^1,\ldots,x^n$ be the global coordinates of $M$. One easily checks that the images of the associated coordinate vectors

\begin{equation}\notag \bd_1|_p, \ldots,\bd_n|_p\in T_p(M) \end{equation}

under $\Theta_{M,p}$ coincide with the partial derivative operators

\begin{equation}\notag \frac{\bd}{\bd x^i}\Big|_p: C^\infty_{M,p} \to \bbr, \quad f \mapsto \frac{\bd f}{\bd x^i}(p). \end{equation}

Thus, it will suffice to show that these partial derivative operators form a basis for the space of derivations. To see that they are linearly independent, it suffices to evaluate an $\bbr$-linear combination

\begin{equation}\notag v^i \frac{\bd}{\bd x^i}\Big|_p =0 \end{equation}

on the coordinate functions $x^j$ to conclude $v^i=0$ for each $i$. To see that the partial derivative operators span the space of derivations, we let a derivation $\delta: C^\infty_{M,p} \to \bbr$ be given. If $f\in C^\infty_{M,p}$ is a function, then by Taylor’s Theorem (see Further Reading, and also here) we may write

\begin{equation}\notag f(x) = f(p) + \frac{\bd f}{\bd x^i}(p)(x^i-p^i) + g(x) \end{equation}

on the domain of $f$, where $g$ is a smooth function in $\mfm_{M,p}^2$. Then, as you may check, we have

\begin{equation}\notag \delta(f) = \delta(x^i)\frac{\bd f}{\bd x^i}(p), \end{equation}

which proves that

\begin{equation}\notag \delta = \delta(x^i) \frac{\bd}{\bd x^i}\Big|_p \end{equation}

in the space of derivations. Thus, the partial derivative operators both span the space of derivations and are linearly independent, which implies that $\Theta_{M,p}$ is an isomorphism. Q.E.D.

In the proof, we noted that the coordinate vectors correspond to partial derivative operators under the isomorphism. (This explains the choice of notation $\bd$ for these vectors.) Let’s extract this fact and put it into a theorem:

Theorem (Partial derivative operators form a basis). Let $(M,p)$ be a pointed manifold and let $x^1,\ldots,x^n$ be local coordinates near $p$. Then the image of the $i$-th associated coordinate vector $\bd_i|_p \in T_p(M)$ under the natural isomorphism

\begin{equation}\notag \Theta_{M,p}:T_p(M) \xrightarrow{\cong} \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{M,p},\bbr) \end{equation}

coincides with the $i$-th partial derivative operator:

\begin{equation}\notag \frac{\bd}{\bd x^i}\Big|_p : C^\infty_{M,p} \to \bbr, \quad f\mapsto \frac{\bd f}{\bd x^i}(p). \end{equation}

Now, at the beginning of this section, the passage from $C^\infty(M)$ to its local rings was motivated by the observation that tangent vectors in $T_p(M)$ are fundamentally local objects, and the local rings encode their properties in a very direct manner compared to $C^\infty(M)$. However, we now move from considerations of individual tangent spaces to globally-defined vector fields. This means that the algebra $C^\infty(M)$ will re-enter the picture.

In fact, all derivations act locally (not just tangent vectors), an observation which is stated precisely in:

Theorem (Derivations act locally). Let $(M,p)$ be a pointed manifold and let

\begin{equation}\notag \lambda: C^\infty(M) \to C^\infty_{M,p} \end{equation}

be the localization map.

- If $\delta: C^\infty(M) \to \bbr$ is a derivation and $f,g\in C^\infty(M)$ are two functions that coincide on an open neighborhood of $p$, then $\delta(f) = \delta(g)$.

- The natural map \begin{equation}\notag \lambda^\ast: \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{M,p},\bbr) \to \Der_\bbr(C^\infty(M), \bbr), \quad \delta \mapsto \delta \circ \lambda \end{equation} is an $\bbr$-linear isomorphism.

In both parts, the real line $\bbr$ is given both a $C^\infty_{M,p}$- and $C^\infty(M)$-module structure obtained by restricting scalars along the evaluation maps at $p$.

To prove (1.), note that by linearity it suffices to prove that $\delta(f)=0$ if $f\in C^\infty(M)$ vanishes on an open neighborhood $U$ of $p$. But, in this case, we may choose a smooth bump function $h\in C^\infty(M)$ which takes the value $1$ on the support of $f$ and which vanishes at $p$. Then, we clearly have $f = hf$, so that

\begin{equation}\notag \delta(f) = \delta(hf) = h(p) \delta(f) + f(p) \delta(h) = 0, \end{equation}

as desired. To prove (2.), note that $\lambda^\ast$ is clearly injective since $\lambda$ is surjective. To prove that $\lambda^\ast$ is surjective, we note by the result in (1.), any derivation $\delta: C^\infty(M) \to \bbr$ “descends” to a derivation $\tl{\delta}: C^\infty_{M,p} \to \bbr$ on the local ring, i.e., there is a derivation $\tl{\delta}$ such that $\delta = \tl{\delta} \circ \lambda$. But then $\lambda^\ast(\tl{\delta}) = \delta$, which is what we wanted to prove. Q.E.D.

This last theorem shows that we could have everywhere replaced derivations over the local ring $C^\infty_{M,p}$ with derivations over the algebra $C^\infty(M)$. In particular, the evident analog of the natural isomorphism

\begin{equation}\notag \Theta_{M,p} : T_p(M) \xrightarrow{\cong} \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{M,p},\bbr) \end{equation}

with $C^\infty_{M,p}$ replaced by $C^\infty(M)$ is still an isomorphism. While this means that we could have avoided all mention of local rings, I believe that this “localization” process is so fundamental in geometry and topology that it’s worth the bit of extra effort to learn about local rings at an early stage of one’s study, even if they aren’t strictly required.

We now have enough to present an algebraic characterization of vector fields on a manifold $M$. To do so, we introduce the $\bbr$-vector space

\begin{equation}\label{der-ast-eqn} \Der_\bbr(C^\infty(M),C^\infty(M)) \end{equation}

of all derivations of the commutative algebra $C^\infty(M)$. Before we relate this object to vector fields, I want you to prove that we’ve just encountered another sheaf:

Exercise. Let the notation be as above.

- Let a derivation $\delta$ in \eqref{der-ast-eqn} be given, and suppose $h\in C^\infty(M)$. We define the scalar product of $h$ and $\delta$, denoted $h\delta$, to be the derivation defined by \begin{equation}\notag (h\delta)(f) = h\delta(f), \end{equation} for $f\in C^\infty(M)$. With respect to this operation and the usual $\bbr$-vector space addition, prove that \eqref{der-ast-eqn} is a $C^\infty(M)$-module.

- Suppose $U$ and $V$ are nonempty open subset of $M$, with $U\subseteq V$. Define an $\bbr$-linear map \begin{equation}\notag s^V_U : \Der_\bbr(C^\infty(V),C^\infty(V)) \to \Der_\bbr(C^\infty(U),C^\infty(U)) \end{equation} by letting $s^V_U(\delta)$ be the derivation on $C^\infty(U)$ with \begin{equation}\notag \left[s^V_U(\delta)\right](f)(p) = \delta(\tl{f})(p) \end{equation} for all $f\in C^\infty(U)$ and $p\in U$, where $\tl{f}$ is any function in $C^\infty(V)$ that coincides with $f$ on an open neighborhood of $p$. Prove that such a function $\tl{f}$ always exists, and that $s^V_U$ is well-defined and $C^\infty(V)$-linear, where the $C^\infty(V)$-module structure on the target of $s^V_U$ is obtained by restricting scalars along the pullback map $C^\infty(V) \to C^\infty(U)$.

- The maps $s^V_U$ in the previous part are called restriction maps. Prove that they have the same properties as the restriction maps $\rho^V_U$ and $r^V_U$ of the sheaves $C^\infty_M$ and $\calx_M$, and thereby conclude that the association \begin{equation}\notag U \mapsto \Der_\bbr(C^\infty(U),C^\infty(U)) \end{equation} is a sheaf of $C^\infty_M$-modules.

Now, for the last fundamental result of this section:

Theorem (Equivalent characterizations of vector fields). Let $M$ be an $n$-dimensional manifold. The natural $C^\infty(M)$-linear map

\begin{equation}\notag \Xi_{M}: \calx(M) \to \Der_\bbr(C^\infty(M),C^\infty(M)), \quad \left[\Xi_M(X)\right](f)(p) = f_{\ast,p}(X_p) \end{equation}

is an isomorphism. If $M$ has a global system of coordinates $x^1,\ldots,x^n$, then the $i$-th coordinate local section $\bd_i$ maps to the $i$-th partial derivative operator

\begin{equation}\label{mirror-eqn} \frac{\bd}{\bd x^i}: C^\infty(M) \to C^\infty(M), \quad f\mapsto \frac{\bd f}{\bd x^i}. \end{equation}

In this case, given a derivation $\delta$, the vector field

\begin{equation}\notag X = \delta(x^i) \bd_i \end{equation}

maps to $\delta$ under $\Xi_M$.

To prove the theorem, we shall take advantage of the fact that the diagram

\begin{equation}\notag \begin{xy} \xymatrix{ \calx(M) \ar[r]^-{\Xi_M} \ar[d]_{r^M_U} & \Der_\bbr(C^\infty(M),C^\infty(M)) \ar[d]^{ s^M_U} \\ \calx(U) \ar[r]^-{\Xi_U} & \Der_\bbr(C^\infty(U),C^\infty(U)) } \end{xy} \end{equation}

commutes, for any nonempty open subset $U$ of $M$ (check this!). In particular, we shall choose $U$ to be an open parametrizable subset of $M$, and prove that $\Xi_U$ is an isomorphism. Then, as $M$ may be covered by such sets, and since both the source and target of $\Xi_M$ are sheaves of $C^\infty_M$-modules, it will follow that $\Xi_M$ is an isomorphism. In essence, we are proving that $\Xi_M$ is more than just a simple isomorphism, it is, in fact, part of an entire isomorphism of sheaves. If this strategy is unclear, I suggest that you carefully work out the details on your own.

Thus, we may as well assume that $M$ has a global coordinate system. But then, the rest of the proof proceeds almost identically to the proof of the main theorem, by arguing that the partial derivative operators \eqref{mirror-eqn} form a basis of the module of derivations. Therefore, I will leave it to you to fill in the details. Once you’ve done so, we can declare: Q.E.D.

Notation. Over an open parametrizable subset $U$ of a manifold $M$, with local coordinates $x^1,\ldots,x^n$, we have seen that the coordinate local section $\bd_i$ corresponds to the derivation $\bd/\bd x^i$ of the algebra $C^\infty(U)$ under the natural isomorphism $\Xi_U$. In the interest of notational brevity and clarity, we shall henceforth intentionally confuse the coordinate local section $\bd_i$ with this partial derivative operator, writing $\bd_i$ when we really mean $\bd/\bd x^i$.

3.5. an interlude on cotangent spaces

In certain situations, it is more natural (in the colloquial sense, not the categorial one) to consider the $\bbr$-linear duals of tangent spaces. In this section, we quickly give the definitions and the basic properties of these dual objects.

To every pointed manifold $(M,p)$ and every morphism $\alpha:(M,p)\to (N,q)$, we have the associated tangent space $T_p(M)$ and pushforward $\alpha_{\ast,p}:T_p(M) \to T_q(N)$. By passing to $\bbr$-linear duals, we obtain the associations

\begin{equation}\notag (M,p) \mapsto T_p^\ast(M) \defeq \Hom_\bbr(T_p(M),\bbr) \end{equation}

and

\begin{equation}\notag \alpha \mapsto ( \alpha_p^\ast \defeq \Hom_\bbr(\alpha_{\ast,p},\bbr) : T_q^\ast(N) \to T_p^\ast(M) ). \end{equation}

The map $\alpha_p^\ast$ is called a pullback; notice that it is written unprimed, in contrast to the pullback

\begin{equation}\notag {\alpha_p^\ast}’: C^\infty_{N,q} \to C^\infty_{M,p} \end{equation}

from the previous section (see \eqref{towel-eqn} and \eqref{towel2-eqn}). The space $T_p^\ast(M)$ is called the cotangent space of $(M,p)$, and its elements are called covectors.

We proved in the previous section that the constructions of tangent spaces and spaces of derivations are functorial. Now, you’ll prove the same thing regarding the construction of cotangent spaces, but with one crucial difference: Passing to cotangent spaces reverses the direction of morphisms.

Exercise. Let $\alpha:(M,p) \to (N,q)$ be a morphism of pointed manifolds.

- If $M=N$ and $\alpha$ is the identity map $\id_M$, prove that $\alpha_{p}^\ast$ is the identity map on cotangent spaces.

- If $\beta:(N,q) \to (L,r)$ is a second morphism of pointed manifolds, prove that \begin{equation}\notag (\beta \circ \alpha)_p^\ast = \alpha_p^\ast \circ \beta_q^\ast. \end{equation}

If you’re keeping track, we now have three functors from the category of pointed manifolds to the category of vector spaces. Two of the functors preserve the direction of morphisms (a property called covariance), while the third reverses their direction (a property called contravariance).

Covectors in $T_p^\ast(M)$ are often produced by taking the differential of a smooth function $f\in C^\infty(M)$ at the point $p$. In detail, note that the pushforward of $f$ at $p$ takes the form

\begin{equation}\notag f_{\ast,p} : T_p(M) \to T_{f(p)}(\bbr). \end{equation}

But the tangent space $T_{f(p)}(\bbr)$ is equal to $\bbr$, and hence the pushforward may be viewed as a covector in the cotangent space $T_p^\ast(M)$. In this case, we often write $df_p$ instead of $f_{\ast,p}$, and call $df_p$ the differential of $f$ at $p$.

There is a natural bilinear pairing between tangent and cotangent spaces given by

\begin{equation}\notag \ang{-,-} : T_p^\ast(M) \otimes_\bbr T_p(M) \to \bbr, \quad (\omega,v) \mapsto \ang{\omega,v} \defeq \omega(v). \end{equation}

This pairing, which is sometimes called a contraction mapping, is used in the following fundamental result:

Theorem (Dual bases of co/tangent spaces). Let $(M,p)$ be a pointed manifold and suppose $x^1,\ldots,x^n$ are local coordiantes near $p$. The differentials $dx^i_p$ of the coordinate functions and the coordinate vectors $\bd_1|_p,\ldots,\bd_n|_p$ satisfy

\begin{equation}\notag \ang{dx^i_p , \bd_j|_p} = \delta^i_j \defeq \begin{cases} 1 & : i=j, \\ 0 & : i\neq j.\end{cases} \end{equation}

In particular, the differentials $dx^1_p,\ldots,dx^n_p$ form a basis of the cotangent space $T_p^\ast(M)$. They are called coordinate covectors.

3.6. Zariski tangent spaces and a summary of the five fundamental functors

If three(!) functors aren’t enough, we now add two more to our repertoire: Let $(M,p)$ be a pointed manifold, and let $\mfm_{M,p}$ be the maximal ideal of the local ring $C^\infty_{M,p}$. We define the Zariski cotangent space at $p$ to be the quotient

\begin{equation}\notag \mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2, \end{equation}

while we define the Zariski tangent space to be its $\bbr$-linear dual:

\begin{equation}\notag (\mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2)^\ast = \Hom_\bbr(\mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2,\bbr). \end{equation}

If $\alpha:(M,p) \to (N,q)$ is a morphism of pointed manifolds, then, as we saw above (see \eqref{towel-eqn} and \eqref{towel2-eqn}), there is the associated pullback map

\begin{equation}\notag {\alpha^\ast_p}’: C^\infty_{N,q} \to C^\infty_{M,p}. \end{equation}

This maps the maximal ideal $\mfm_{N,q}$ into the maximal ideal $\mfm_{M,q}$, and hence it descends to a well-defined $\bbr$-linear map

\begin{equation}\notag {\alpha^\ast_p}’’: \mfm_{N,q}/\mfm_{N,q}^2 \to \mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2 \end{equation}

which is also called a pullback map. Applying the $\bbr$-linear dual to this previous map, we obtain an $\bbr$-linear map

\begin{equation}\notag \alpha’'_{\ast,p} : (\mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2)^\ast \to (\mfm_{N,q}/\mfm_{N,q}^2)^\ast \end{equation}

on Zariski tangent spaces that we call a pushforward.

Let’s summarize!

Five fundamental functors. Let $(M,p)$ be a pointed manifold and $\alpha:(M,p) \to (N,q)$ a morphism of pointed manifolds.

- We have tangent spaces and their pushfowards: \begin{equation}\notag (M,p) \mapsto T_p(M) \end{equation} and \begin{equation}\notag \alpha \mapsto \left(\alpha_{\ast,p}: T_p(M) \to T_q(N)\right). \end{equation}

- We have cotangent spaces and their pullbacks: \begin{equation}\notag (M,p) \mapsto T_p^\ast(M) \end{equation} and \begin{equation}\notag \alpha \mapsto \left( \alpha_p^\ast: T_q^\ast(N) \to T_p^\ast(M)\right). \end{equation}

- We have spaces of derivations and their pushforwards: \begin{equation}\notag (M,p) \mapsto \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{M,p},\bbr) \end{equation} and \begin{equation}\notag \alpha \mapsto \left(\alpha’_{\ast,p}: \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{M,p},\bbr) \to \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{N,q},\bbr)\right). \end{equation}

- We have Zariski tangent spaces and their pushforwards: \begin{equation}\notag (M,p) \mapsto (\mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2)^\ast \end{equation} and \begin{equation}\notag \alpha \mapsto \left(\alpha’'_{\ast,p}: (\mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2)^\ast \to (\mfm_{N,q}/\mfm_{N,q}^2)^\ast\right). \end{equation}

- We have Zariski cotangent spaces and their pullbacks: \begin{equation}\notag (M,p) \mapsto \mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2 \end{equation} and \begin{equation}\notag \alpha \mapsto \left({\alpha_p^\ast}’’: \mfm_{N,q}/\mfm_{N,q}^2 \to \mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2\right). \end{equation}

In the previous two sections, we established that the constructions in (1.), (2.) and (3.) are functorial, with (1.) and (3.) preserving the direction of morphisms, and (2.) reversing them. In the next exercise, you will prove that the constructions in (4.) and (5.) are also functorial.

Exercise. Let $\alpha:(M,p) \to (N,q)$ be a morphism of pointed manifolds.

- If $M=N$ and $\alpha$ is the identity map $\id_M$, prove that the pushforward $\alpha_{\ast,p}’’$ and pullback ${\alpha_p^\ast}’’$ are the identity maps.

- If $\beta:(N,q) \to (L,r)$ is a second morphism of pointed manifolds, prove that we have \begin{equation}\notag (\beta \circ \alpha)_{\ast,p}’’ = \beta_{\ast,q}’’ \circ \alpha_{\ast,p}’’ \end{equation} and \begin{equation}\notag {(\beta\circ \alpha)_{p}^\ast}’’ = {\alpha^\ast_p}’’ \circ {\beta^\ast_{q}}’’. \end{equation}

With reference to the numbering in the summary given above, we have shown that the constructions in (1.) and (3.) are (naturally) isomorphic via the isomorphisms $\Theta_{M,p}$. In this section, we will construct three more natural isomorphisms, this time between (1.) and (4.), (3.) and (4.), and (2.) and (5.).

For the natural isomorphism between cotangent spaces (2.) and Zariski cotangent spaces (5.):

Theorem (Cotangent spaces $=$ Zariski cotangent spaces). Let $(M,p)$ be a pointed manifold. The natural map

\begin{equation}\notag \Phi_{M,p}: \mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2 \to T_p^\ast(M), \quad f+\mfm_{M,p}^2 \mapsto df_p \end{equation}

is an $\bbr$-linear isomorphism.

The proof strategy is the same as it was for the theorem relating tangent spaces to spaces of derivations: Reduce to the case $M=\bbr^n$ by using naturality and the fact that both the domain and codomain of the alleged isomorphism may be restricted (up to isomorphism) to open parametrizable subsets.

You will first establish the “naturality” part in:

Exercise. Let $\alpha:(M,p) \to (N,q)$ be a morphism of pointed manifolds. Prove that the diagram

\begin{equation}\notag \begin{xy} \xymatrix{ \mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2 \ar[r]^{ \Phi_{M,p}} & T_p^\ast(M) \\ \mfm_{N,q}/\mfm_{N,q}^\ast \ar[r]_{\Phi_{N,q}} \ar[u]^{ {\alpha_p^\ast}’’} & T_q^\ast(N) \ar[u]_{\alpha_p^\ast}} \end{xy} \end{equation}

commutes.

Also, we need:

Theorem (Zariski cotangent spaces on open subsets). Let $(M,p)$ be a pointed manifold, $U\subseteq M$ a nonempty open subset containing $p$, and $\iota:U \to M$ the (smooth) inclusion map. The pullback

\begin{equation}\notag {\iota_p^\ast}’’: \mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2 \to \mfm_{U,p}/\mfm_{U,p}^2 \end{equation}

on Zariski cotangent spaces is an $\bbr$-linear isomorphism.

In fact, we already saw in the previous section that $\iota$ induces an isomorphism $C^\infty_{M,p}\cong C^\infty_{U,p}$ of local rings. Thus, there isn’t really anything to prove regarding this last theorem.

Now, let’s prove the theorem by showing that the map $\Phi_{M,p}$ is an isomorphism. As we already noted, there is no loss in generality in assuming that $M=\bbr^n$, with global coordinates $x^1,\ldots,x^n$. Given a function $f\in C^\infty(U)$ defined on an open neighorhood $U$ of $p$ that vanishes at $p$, we may use Taylor’s Theorem (for a third time) to write

\begin{equation}\notag f(x) = \frac{\bd f}{\bd x^i}(p) (x^i-p^i) + g(x), \end{equation}

where $g\in C^\infty(U)$ is a function contained in $\mfm_{M,p}^2$. Thus, the coset $f + \mfm_{M,p}^2$ in the Zariski cotangent space is equal to

\begin{equation}\notag f + \mfm_{M,p}^2 = \frac{\bd f}{\bd x^i}(p) (x^i-p^i) + \mfm_{M,p}^2. \end{equation}

This shows that the cosets of the (shifted) coordinate functions $x^i-p^i$ span the Zariski cotangent space. However, these cosets map to the coordinate covectors $dx^i_p$ in $T_p^\ast(M)$, which form a basis. Thus, $\Phi_{M,p}$ is an isomorphism. Q.E.D.

Let’s extract a useful fact from the proof and place it in its own theorem:

Theorem (Coordinate functions form a basis). Let $(M,p)$ be a pointed manifold and let $x^1,\ldots,x^n$ be local coordinates near $p$. Then the image of the coset of $x^i - p^i$ under the natural isomorphism

\begin{equation}\notag \Phi_{M,p}: \mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2 \xrightarrow{\cong} T_p^\ast(M) \end{equation}

coincides with the $i$-th coordinate covector $dx^i_p$.

Let’s now turn to the relation between tangent spaces and Zariski tangent spaces:

Theorem (Tangent spaces $=$ Zariski tangent spaces). Let $(M,p)$ be a pointed manifold. There is a natural isomorphism

\begin{equation}\notag \Omega_{M,p}: T_p(M) \xrightarrow{\cong} (\mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2)^\ast \end{equation}

of $\bbr$-vector spaces.

Notice that I did not give a formula for the map $\Omega_{M,p}$. This is because I want you to prove the theorem on your own:

Exercise. By dualizing the natural isomorphism $\Phi_{M,p}$ between cotangent spaces and Zariski cotangent spaces, and by using the natural isomorphism between a finite-dimensional vector space and its double dual, prove the previous theorem.

Now, we only have one more natural isomorphism that we need to construct, between Zariski tangent spaces and spaces of derivations. This, in turns out, may be obtained as a corollary of a purely algebraic result. To state it, we need an algebraic analog of the category of pointed manifolds:

Definition. We define a pointed algebra to be a pair $(A,\dev)$ consisting of a commutative $\bbr$-algebra $A$ and a homomorphism $\dev: A \to \bbr$ of $\bbr$-algebras. A morphism of pointed algebras, denoted $\mu:(B,\zeta) \to (A,\dev)$, is a homomorphism $\mu:B\to A$ of commutative $\bbr$-algebras such that $\dev \circ \mu = \zeta$.

There is an evident construction that carries the category of pointed manifolds to the category of pointed algebras. Indeed, given a pointed manifold $(M,p)$, we have

\begin{equation}\notag (M,p) \mapsto (C^\infty_{M,p}, \dev_p), \end{equation}

where $\dev_p: C^\infty_{M,p} \to \bbr$ is the homomorphism that evaluates a germ at $p$. Given a morphism $\alpha:(M,p) \to (N,q)$ of pointed manifolds, we send it to the pullback

\begin{equation}\notag \alpha \mapsto \left({\alpha_p^\ast}’: (C^\infty_{N,q}, \dev_q) \to (C^\infty_{M,p}, \dev_p)\right) \end{equation}

introduced in an earlier section (see \eqref{towel-eqn} and \eqref{towel2-eqn}). You will now prove that this construction is functorial:

Exercise. Let the notation be as above.

- Check that the pullback ${\alpha_p^\ast}’$ really is a morphism of pointed algebras.

- If $M=N$ and $\alpha$ is the identity map $\id_M$, prove that ${\alpha_p^\ast}’$ is the identity map.

- If $\beta:(N,q)\to (L,r)$ is a second morphism of pointed manifolds, prove that we have \begin{equation}\notag {(\beta\circ \alpha)_p^\ast}’ = {\alpha_p^\ast}’ \circ {\beta_q^\ast}’. \end{equation}

In the algebraic category of pointed algebras, there is an evident analog of Zariski tangent spaces and pushforwards. To describe them, suppose that $\mu:(B,\zeta)\to (A,\dev)$ is a morphism of pointed algebras and that we set $\mfn = \ker{\zeta}$ and $\mfm = \ker{\dev}$. Then $\mu(\mfn) \subseteq \mfm$, and so $\mu$ descends to an $\bbr$-linear map

\begin{equation}\notag \mu_\dev^\ast : \mfn/\mfn^2 \to \mfm/\mfm^2 \end{equation}

which, after dualizing, yields an $\bbr$-linear map

\begin{equation}\notag \mu_{\ast,\dev} : (\mfm/\mfm^2)^\ast \to (\mfn/\mfn^2)^\ast \end{equation}

that we call a pushforward map. These purely algebraic Zariski tangent spaces and pushforwards have the expected functorial properties, which you will prove in the following exercise:

Exercise. Let the notation be as above.

- If $A=B$ and $\mu$ is the identity map $\id_A$, prove that the pushforward $\mu_{\ast,\dev}$ is the identity map.

- If $\nu:(C,\eta) \to (B,\zeta)$ is a second morphism of pointed algebras, prove that we have \begin{equation}\notag (\mu \circ \nu)_{\ast,\dev} = \nu_{\ast,\zeta} \circ \mu_{\ast,\dev}. \end{equation}

Now, in order to relate Zariski tangent spaces to spaces of derivations, we use the following fundamental algebraic result:

Theorem (Linearization of derivations). Let $(A,\dev)$ be a pointed algebra, set $\mfm = \ker{\dev}$, and write $\pi: A \to \mfm/\mfm^2$ for the $\bbr$-linear map with

\begin{equation}\notag f\mapsto (f - \dev(f)) + \mfm^2. \end{equation}

Then, the natural $\bbr$-linear map

\begin{equation}\notag \Psi_{A,\dev}: \Hom_\bbr(\mfm/\mfm^2, \bbr) \to \Der_\bbr{(A,\bbr)}, \quad \vartheta \mapsto \vartheta \circ \pi, \end{equation}

is an isomorphism, where $\bbr$ is given an $A$-module structure by restricting scalars along $\dev$.

It is an interesting exercise to show that $\Psi_{A,\dev}$ is actually well-defined, i.e., that $\vartheta\circ \pi$ is a derivation. I suggest that you try it on your own. After that, we observe that $\Psi_{A,\dev}$ is clearly injective, since $\pi$ is surjective. For surjectivity of $\Psi_{A,\dev}$, we note that any derivation $\delta$ annihilates the kernel of $\pi$, and hence descends along $\pi$ to an $\bbr$-linear map $\vartheta:\mfm/\mfm^2 \to \bbr$ (why?). But then $\Psi_{A,\dev}(\vartheta)=\delta$, which proves $\Psi_{A,\dev}$ is surjective. Q.E.D.

By specializing our purely algeraic result to algebras of smooth functions, we get the desired result:

Theorem (Zariski tangent spaces $=$ derivations). Let $(M,p)$ be a pointed manifold and write $\pi: C^\infty_{M,p} \to \mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2$ for the $\bbr$-linear map with

\begin{equation}\notag f \mapsto (f - f(p)) + \mfm_{M,p}^2. \end{equation}

Then, the natural $\bbr$-linear map

\begin{equation}\notag \Psi_{M,p}: \Hom_\bbr(\mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2, \bbr) \to \Der_\bbr{(C^\infty_{M,p},\bbr)}, \quad \vartheta \mapsto \vartheta \circ \pi, \end{equation}

is an isomorphism.

We end this (long) post with an observation about the mutual compatibility of the three natural isomorphisms

\begin{equation}\notag \Theta_{M,p} : T_p(M) \xrightarrow{\cong} \Der_\bbr(C^\infty_{M,p},\bbr), \end{equation}

and

\begin{equation}\notag \Omega_{M,p} : T_p(M) \xrightarrow{\cong} (\mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2)^\ast, \end{equation}

and

\begin{equation}\notag \Psi_{M,p}: \Hom_\bbr(\mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2, \bbr) \xrightarrow{\cong} \Der_\bbr{(C^\infty_{M,p},\bbr)}. \end{equation}

Exercise. Prove that the composite natural isomorphism

\begin{equation}\notag T_p(M) \xrightarrow{\Omega_{M,p}} (\mfm_{M,p}/\mfm_{M,p}^2)^\ast \xrightarrow{\Psi_{M,p}} \Der_\bbr{(C^\infty_{M,p},\bbr)} \end{equation}

is equal to $\Theta_{M,p}$.

3.7. further reading

Just how far can the algebraic treatment of smooth manifolds be pushed? To see how deep this rabbit hole goes, I would recommend taking a look at Nestruev’s fascinating textbook (3). In particular, this book contains a complete proof of a more general version of the Serre-Swan Theorem.

The version of “Taylor’s Theorem” that I refer to in this post may be found in Lee’s comprehensive book (4), though do also check out Nestruev’s book for a related result and the link to the nLab.

As I mentioned in the introduction, algebra and geometry become truly equivalent in scheme-theoretic algebraic geometry. Here, the standard reference in the field is, of course, Hartshorne’s book (5). However, I don’t think this book is well-suited for an introduction to algebraic geometry. Instead, I would recommend one of my favorite texts, Kunz’s book (6). You will also find a very nice treatment of projective modules in this last reference.

3.8. references and footnotes

-

V. Guillemin and A. Pollack. Differential topology. AMS Chelsea Publishing. Providence, RI, 2010. ↩

-

M. F. Atiyah and I. G. MacDonald. Introduction to Commutative Algebra. Advanced Book Program, Westview Press, 1969. ↩

-

J. Nestruev. Smooth manifolds and observables. Second edition. Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 220. Springer, Cham, 2020. ↩

-

J. M. Lee. Introduction to smooth manifolds. Second edition. Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 218. Springer, New York, 2013. ↩

-

R. Hartshorne. Algebraic geometry. Graduate Texts in Mathematics, No. 52. Springer-Verlag, New York-Heidelberg, 1977. ↩

-

E. Kunz. Introduction to commutative algebra and algebraic geometry. Modern Birkhäuser Classics. Birkhäuser/Springer, New York, 2013. ↩